Thanksgiving has become an important institution in America, from roasted turkey and pumpkin pie to arguments across the dinner table with your out-of-touch aunt and the always popular 3:30 nap, nothing says you're thankful like this homegrown holiday.

In fact, Thanksgiving is much more than just a holiday, it’s a piece of American history, started by the Pilgrims on their arrival in the new world, and held to celebrate both their first year of independence from England and the Anglican Church, as well as the relationships they had built with their new friends, the Wampanoag.

Or so you thought.

Despite the reality of American history being much more complicated, especially when it comes to relations—if you can call them that—with the native people who occupied this land long before we moved in uninvited, there is an even larger misconception about the origin of Thanksgiving.

Regardless of what we may have learned from elementary school teachers, television, and maybe even our out-of-touch aunt, there is another story that predates the Puritan pilgrimage to the new world, one that goes decades further back to the Spanish explorers and the true first European settlement in America—St. Augustine.

Many think of the Pilgrims as being the first Europeans to build a community on North American soil, but that is far from the truth. On their arrival in 1620, another colony in America was already fifty years old and thriving, many miles south along what is now Florida’s eastern coastline.

That colony is St. Augustine. Founded in 1565 by Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, it has been occupied ever since, even despite changing hands between the Spanish and the British several times before Florida was acquired by the U.S. in 1819—making it by far the oldest continuously occupied European settlement in the Americas.

In fact, St. Augustine is a city of firsts. The first city government, first school, first hospital, first city plan, first Parrish church, and even the first mission to the native populations. When it comes to the first European influences in the Americas, the “Ancient City'' has all the bases covered.

But what about Thanksgiving?

There is no arguing that the Spanish settlers in St. Augustine predated the Pilgrims in New England, but Thanksgiving is about more than just who got there first, it’s about coming together with the people you care about, making new friends, and celebrating everything you have to be thankful for.

We all know how the Pilgrim’s First Thanksgiving played out, we’ve seen it time and time again, but what about the Spanish in St. Augustine? Could they have had the REAL First Thanksgiving?

Turns out they did, and long before the Pilgrims plucked their first turkey, the Spanish colonizers in St. Augustine were celebrating how thankful they were to be alive and healthy in the new world.

In fact, this celebration, held in the form of a Catholic mass followed by a giant feast, was not that different from the notorious meal that put the Pilgrims on the map.

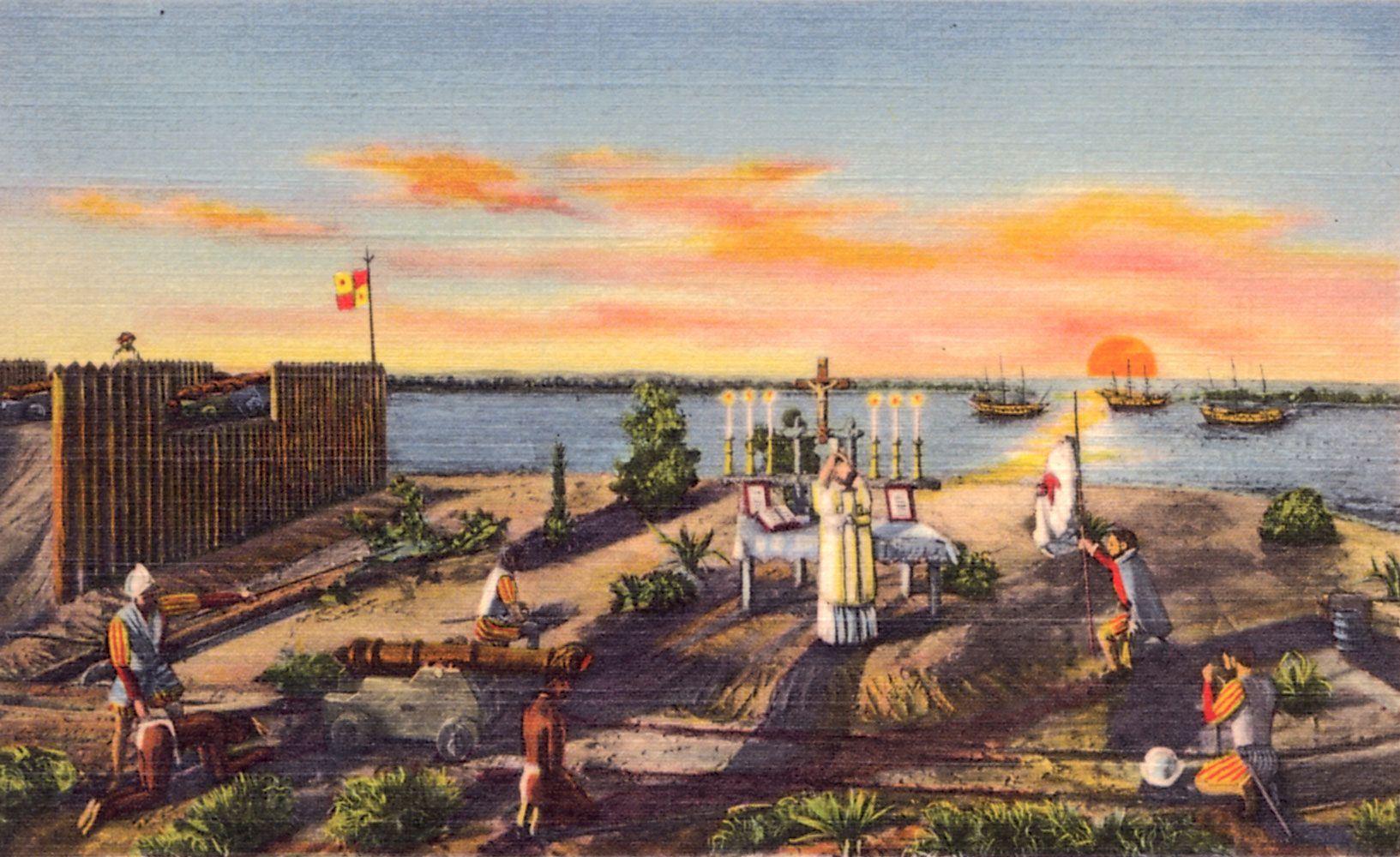

When Menéndez de Avilés and 800 Spanish settlers first came ashore in 1565, they had a lot to celebrate. Not only had they survived the long voyage—which was an accomplishment in those days—but they were also coming ashore during the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, a very important day according to the church calendar.

The landing party, led by St. Augustine’s first pastor, Father Francisco Lopez de Mendoza Grajales, came together and celebrated the traditional feast day with a Mass of Thanksgiving, a religious ceremony that would have looked similar to a Spanish Catholic mass held today.

It wasn’t until after the ceremony, though, that the real Thanksgiving would commence, as Menéndez de Avilés not only laid out a great feast for both his men and the settlers, but also for the Timucua, a native tribe who they had traded with in the past, and had met upon their arrival.

The meal, which would have looked much different than the traditional turkey and stuffing we know today, would have likely been made up of the same food the settlers had been enjoying on the voyage. This included hard sea biscuits, red wine, and a hearty stew made from salted pork and garbanzo beans known as cocido.

If any traditional Thanksgiving options had been available, it would have had to have been brought by the Timucua, who not only had access to turkey, but to other staples such as maize (corn), beans, and squash. However, it is not documented whether or not they were part of the meal preparation.

They did, on the other hand, participate in mass. What exactly the Timucua must have thought of the foreign religious ceremony is not known, but in his journals, Father Lopez noted that “the Indians imitated all they saw done,” likely in an attempt to initiate a peaceful relationship with the Spanish.

Of course, from the Spanish’s perspective, this communion with the Timucua would have been little more than the first step in an aggressive Christian conversion strategy, but the similarities between their peace-offering and the Pilgrims breaking bread with the Wampanoag in Plymouth cannot be ignored.

This, coupled with all of the other similarities, still leaves most of us with one question: why isn’t the Thanksgiving feast in St. Augustine recognized as America’s first?

Despite the event being well-documented, the irony of a Catholic mass being the true inspiration for the Thanksgiving holiday, and not the famous feast of the Puritan Pilgrims—who were notoriously anti-Catholic—is not lost on history, and has even led to a great deal of controversy.

It is only recently, thanks to the hard work of a few historians in Florida, that the real history has finally made it into the mainstream. Now, many other historians have started to back the claim that St. Augustine, and not Plymouth, is the true source of the American tradition.

However, tradition is tradition, and the story of the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag has become so closely entwined with the holiday and its folklore, that the historical accuracy has taken a backseat to time-honored festivities and beloved cultural motifs.

Today, the only memory of the real first Thanksgiving is marked by a 250 foot cross at the Mission of Nombre de Dios, a small church that sits at the original landing site of the settlers, just 300 yards north of the famously haunted Castillo de San Marcos, where the rest of the city’s sordid history has lingered for more than three centuries.

With such a long and complicated past, there is no shortage of restless spirits in St. Augustine. From haunted hotels to pirate poltergeists, and perhaps everything in between, there is not a square inch of the “Ancient City” that doesn’t hold some vestige of the people that came before us.

Considering so much haunted history, it would be hard to believe that some vestige of the First Thanksgiving hasn’t been left behind, or even attached itself to one of the many locations that are still tied to the holiday’s roots.

Well, maybe it has.

The settlers themselves that participated in the First Thanksgiving may not haunt the city, but the descendants of the Timucua who once greeted them in peace certainly do. Despite friendly relations during that first mass of thanksgiving, it wasn’t long before the Spanish’s relationship with the Timucua began to sour.

Proof of this fragile relationship still stands today in the form of the Castillo de San Marcos, which was not only built from the labor of the Timucua but at one point served as an internment prison for those who would not concede to Spanish rule. Not just the Timucua either, but Seminole, Apache, and many others, as well.

Because of this, many native lives were lost at the Castillo, a lasting reminder of how the First Thanksgiving, as well as the values it tried to represent, quickly disintegrated. A theme that would, unfortunately, play out again a thousand miles north with the Pilgrims in New England.

Of the Native American spirits that are left behind, a grim reminder of many tribe’s disintegrations at the hands of plague, wars, and the Spanish, the most well-known linger in the Castillo de San Marcos itself, only a few hundred yards from the First Thanksgiving.

There, the spirits of Native American men call out from the jail cells and torture chambers of old. Some even speak of a Seminole chief, known as Osceola’s, who wanders the grounds at night, and has even been seen jumping from the ramparts, perhaps still hoping for freedom.

It just goes to show that, while St. Augustine may have been the home of the real First Thanksgiving, it came at a cost and one that we are still paying for to this day. So whether it was the Pilgrims in Plymouth or the Spanish in St. Augustine, what is important is understanding the truth behind this complicated holiday.