In an age when reliance on technology and modern amenities has become an unavoidable necessity in our daily lives, it is no wonder that people have started to flock to tourist destinations that seek to offer a very different experience.

These living history museums, frozen in time, offer an in-depth, live-action look into the lives of our ancestors, and have become popular spots to not only teach hands-on history but to showcase a standard of life that was once the norm.

Colonial Williamsburg, Ponce de Leon’s Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park, and Conner Prairie are just some of the most recognizable names when it comes to the living history experience, but few have as much notoriety as the Plimoth Plantation in Plymouth, Massachusetts, where history not only comes alive but continues to haunt the living.

Plymouth Massachusetts, known to many as “America’s Hometown,” sits only 40 miles south of Boston, and holds an important place in American history. Not only is it both the landing site of the Pilgrims and the oldest European settlement in New England, but it is also the location of the First Thanksgiving, the feast that inspired the now celebrated holiday.

Founded in 1620 and named by the English explorer John Smith, Plimoth was designed to be a new start for the Pilgrims, a small group of separatist Puritans that had left their home in England to avoid religious persecution from the Anglican Church.

In the Americas they saw a space where they could practice their faith without fear, and live out their lives according to the values and practices that they held. Plimoth grew from this dream, and with its success soon attracted others, becoming a bustling community in only a few short years and building the blueprint for other early American colonies.

Today, the town of Plimoth—now more commonly spelled “Plymouth”—is home to over 60,000 people, embracing its heritage through a focus on history, education, and preservation. It’s said that you don’t have to dig deep in New England to find America’s roots, but few spots embody this spirit as much as Plimoth Plantation.

The Plimoth Patuxet Museum, known colloquially as Plimoth Plantation, is one of the premier educational destinations in all of Massachusetts, serving an impressive 90,000 educators and students annually.

The idea of a living history museum, where staff would reenact the time of the Pilgrims with meticulous detail and historical accuracy, came from Boston stockbroker and history buff Henry Hornblower II, who began the project in 1947 on the shore of Plymouth Bay where the Mayflower once landed.

Visitors to Plimoth Plantation have the opportunity to see history come alive, watching and interacting with the daily lives of the Pilgrims, as well as the native Wampanoag people who had been living on the land for tens of thousands of years and traded with early settlers.

These live exhibits include daily chores, town politics, and interactions between Pilgrims and Wampanoag. It was the Plimoth Plantation’s aim to put history in people’s hands, not behind glass, allowing visitors to experience 17th-century life for themselves—including a lifesize reconstruction of the Mayflower.

Of course, with this much history spread around, covering a piece of land with a long and complicated history, it comes as no surprise that there may be more than just tourists and reenactors walking these hallowed grounds.

In fact, the redacted lives of Pilgrims and Wampanoag may take center stage during the daylight hours, but it’s in the dead of night when America’s real past comes out to play in and around Plimoth Plantation.

Outside of the museum itself, where the sordid history of America’s early beginning stays neat and orderly, packaged and sold, is the real Plimoth Plantation. A place where memories of the past have taken on a different form, one that maybe shines a less favorable light on America’s early settlers.

In truth, Plymouth has its layers, and it isn’t until you dig down deeper that you discover the plague that nearly wiped out the Wampanoag, the witch trials that spread over Puritan New England, or even the everyday struggles of surviving in a new, unfamiliar world. In short, there was no shortage of brutal and unnecessary deaths.

Because of this, Plimoth Plantation, settled near the shores where the Mayflower first landed, has become the epicenter for a world that refuses to be forgotten, where artifacts of the past can be found around every corner, and the spirits of many eras and nations are determined to make themselves known.

Across the plantation strange voices can be heard in the night, tools and artifacts will move from one place to another or even disappear completely, and people dressed in period clothing can be seen walking the grounds long after the staff has clocked out.

But the hauntings aren’t confined to this one street. In fact, a square inch free of restless spirits in and around Plymouth is few and far between. But one can’t talk about the ghosts of Plymouth without mentioning one of the most notorious spots for the paranormal—Burial Hill.

Just a few miles from the heart of Pilgrim territory lies one of the most notoriously haunted cemeteries in all of New England. Burial Hill, sitting atop a grassy knoll that overlooks the bay and the colony below, had a big part to play in the long and sordid history of Plymouth.

Originally the location of Plymouth’s first fort, the space has served many other purposes over the years, from a meeting house to a courthouse, and even a church. It wasn’t until 1637, nearly two decades after the colony was established, that it took on its final role as a cemetery.

It is here that many descendants of the Mayflower are buried, dead not just from old age, but from disease, starvation, and even the hands of others. The first years of the settlement were not easy, and it wasn’t long before the cemetery began to fill, one grave at a time.

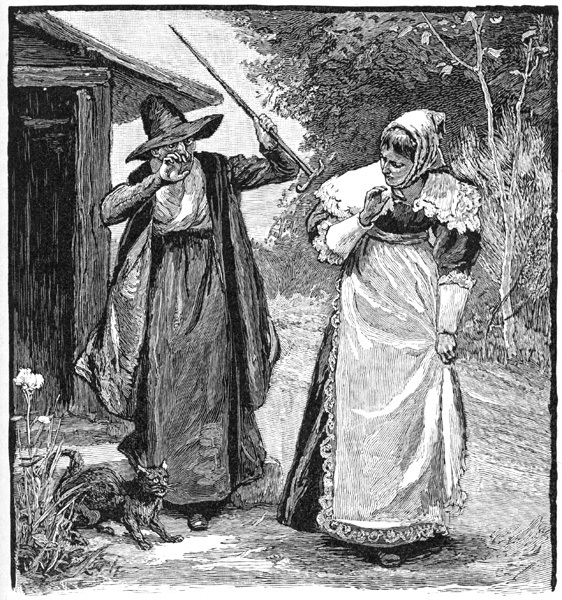

One such occupant is Thomas Southward Howland who, as legend tells it, made the mistake of crossing the notorious Mother Crewe, a rumored witch who lived in the woods on Howland’s property. After forcing her out, she is said to have told him “they’ll dig your grave on Burial Hill.”

It seems that Mother Crewe, witch or not, was on to something because it was only hours later that Thomas Southward Howland fell from his horse and joined his forefathers on Burial Hill, where he is still found today, wandering between the headstones and cursing the witch who cut his life short.

This famous cemetery is no stranger to tragedy, as you can see, but few of its inhabitants have met an end as tragic as the 70 men who share a mass grave beneath the massive obelisk that crowns the top of the hill, victims of a horrific accident that still haunts the town’s descendants to this day.

In 1778, the Brigadier General Arnold, a ship crewed by 105 men, ran aground in Plymouth Bay during a terrible blizzard. The men were stranded in freezing weather, and the residents of Plymouth, unable to reach them, could do nothing but watch from afar as the weather ravaged the ship for days on end. By the time that help arrived, 70 of the men had frozen to death.

Of the men who survived, one of them was the Captain himself, James Magee. Magee, so racked with guilt, spent the rest of his life asking to be buried with his crew, but, unfortunately, his wish was never fulfilled. Which is likely why he still haunts the cemetery today, trying to join his lost men.

Of the many others who have been buried on Burial Hill, all the way up until the last body was laid to rest in 1957, not all are seen, but it is those who have held on over the centuries, reminding us of the real history of Plymouth, that we are the most haunted by.