"You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of underdone potato. There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

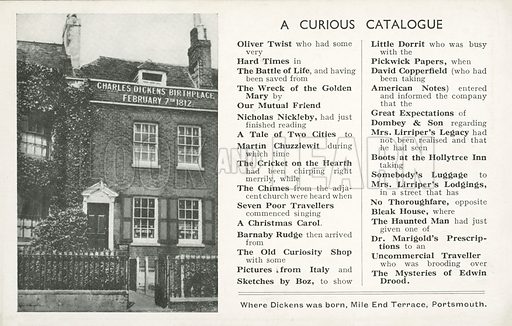

Perhaps not the most iconic line in Charles Dickens’ festive ghost story A Christmas Carol from 1843, but an important one.

Dickens had a fascination with the supernatural, almost an obsession. He wrote dozens of ghost stories throughout his illustrious writing career. He attended numerous séances, and he was even one of the founding members of the esteemed Ghost Club of London – an organization that still exists to this day.

He was fervent in finding out all he could on the weird and bizarre. There was, however, an issue with his hunt.

He didn’t believe in any of it.

That is to say, he went out of his way to debunk any supernatural shenanigans in the hope of finding a real ghost. As he has said so himself, “Don’t suppose that I am so bold and arrogant as to settle what can and what cannot be, after death.”

Despite the numerous ghost stories he has written, he always wrote them with an air of skepticism and scientific logic. So, logically it would make sense that during the era of the massive cultural wave that was spiritualism, his ghost stories would be revered. Like all of his other works, they were devoured by the public in praise and admiration.

Of course, it wasn’t as if this fascination and hesitation of the supernatural came out of the blue one day.

No, in fact, this journey began, like all things do, during his childhood.

Dickens was never one to be vocal about aspects of his childhood, or his entire childhood altogether. He did claim that his childhood was what developed, as he called it, “dark corners” of his mind.

And his fascination with ghosts was no different.

Dickens recalled having a nanny, named Miss Mercy, who would terrify his bedside with tales of ghosts and goblins at night. One that was ingrained into his mind was the horrific tale of Captain Murderer, who would make pies out of his wives. Miss Mercy would add to the gruesome story by clawing at the air and making low groans.

It was absolutely petrifying for the then-novel novelist. As he would aptly put into words, “Her name was Mercy, though she had none on me.”

How cruel that such tales that would scare him into the night would fascinate him in his teen years, readily buying every new issue of horror magazine The Terrific Register. Even though they left him “unspeakably miserable, and frightened my very wits out of of my head.”

Though, it would seem that his wits did recover in later years as he threw away the folly of anything paranormal. He rejected the notions of spiritualism and focused on the art of mesmerism.

In other words, hypnotism. It was this and the ideas of scientific theory that gave him the hypothesis that ghosts and hauntings were little more than a raw disorder of the mind. So sort of hysterical nervousness.

Or, as Ebenezer Scrooge would say, “an undigested bit of beef.”

Regardless, Dickens never claimed to be right or even an expert on his views of the supernatural, he was adamant about the research of such fields of the unexplainable, not only to disprove but perhaps in the off chance, to prove. That is where the Ghost Club came in.

The foundations of the Ghost Club were rooted in 1855, with a group of men at Trinity College in Cambridge who had discussions on the paranormal. Seven years later in 1862, the Ghost Club was officially launched to investigate and discuss supposed paranormal events that were happening in London.

Of course, it received marginal ridicule from the paper, but a sort of validity was formed with Charles Dickens being one of its earliest members. Some may even argue that Dickens was one of its founders.

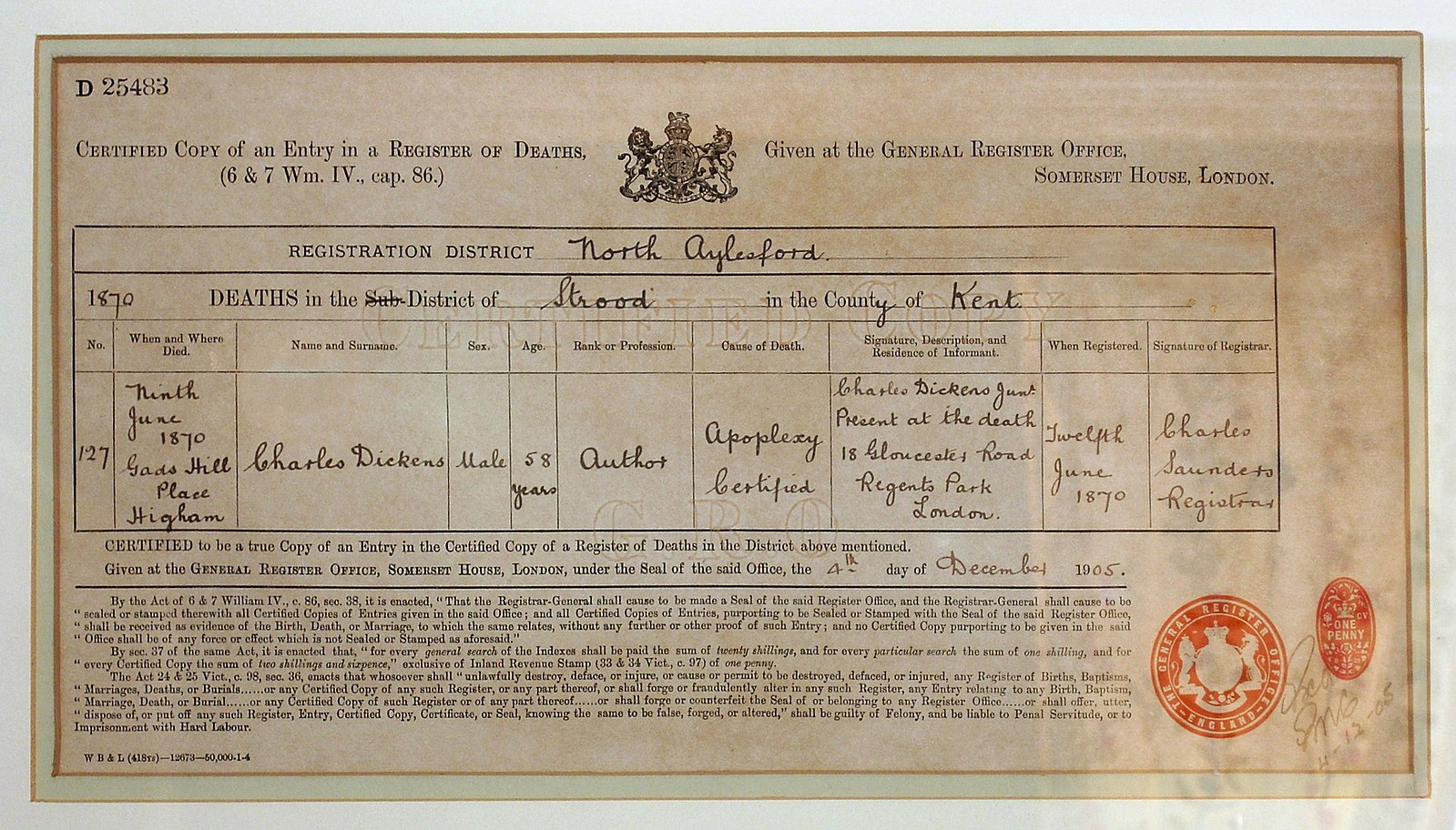

Perhaps that’s why the Ghost Club disbanded for more than a decade after Charles Dickens’ death in 1870.

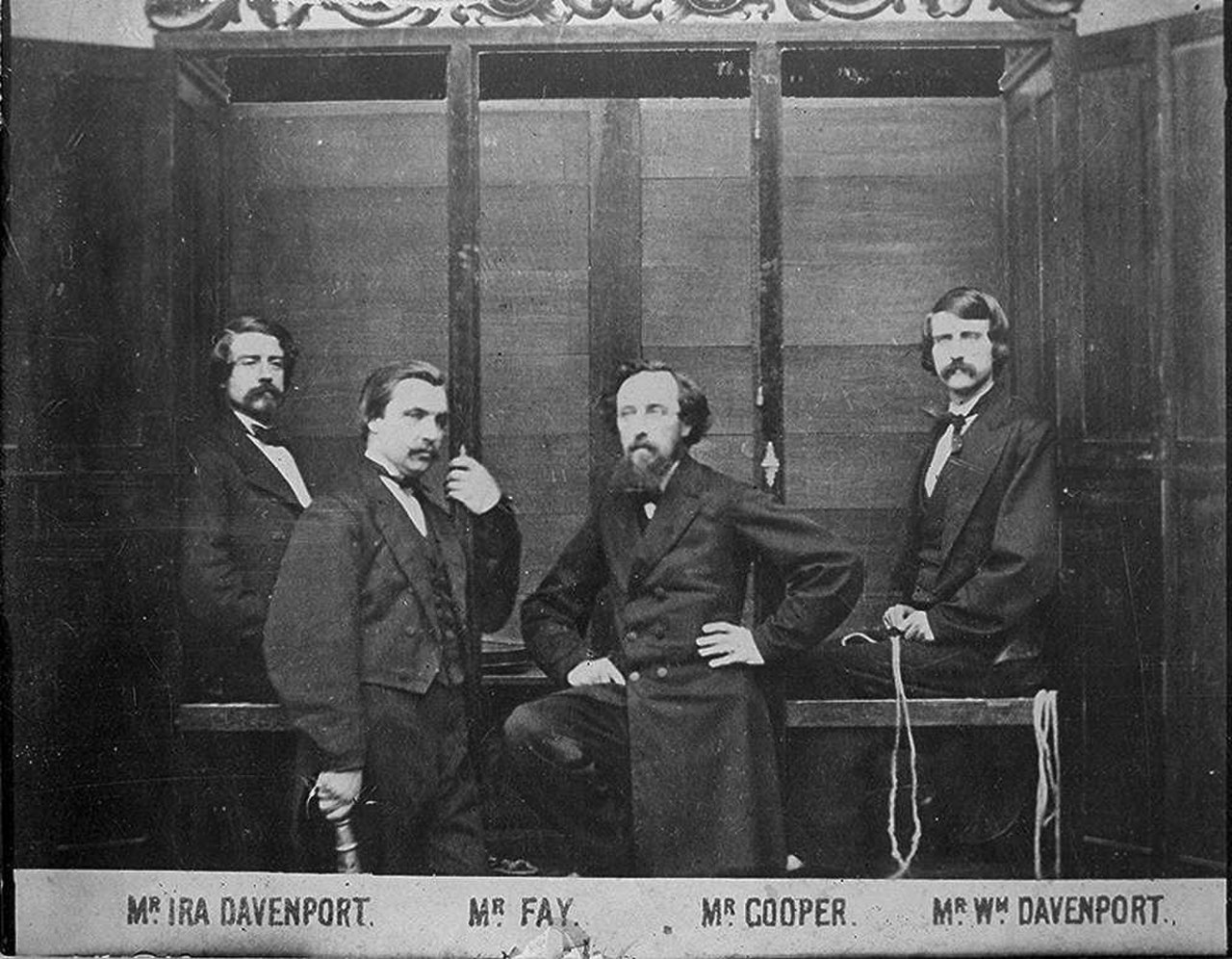

One of the Ghost Club’s earliest investigations was that of the Davenport Brothers.

At the time, they were a pair of American magicians who performed magic tricks under the aid of what they claimed to be supernatural forces.

One of their most well-known tricks was that of the spirit cabinet. The brothers would be tied and bound in a cabinet surrounded by musical instruments. The cabinet would close and the instruments would begin to play in the cabinet. Once it was reopened, it would reveal that the brothers were still tied and bound.

The only explanation was that spirits from beyond the grave were playing the instruments.

When the brothers came to England, the Ghost Club arrived not far behind them, desperate to debunk their ghost box. With aid from other magicians, the Club recreated the spirit cabinet to show the inner workings of the trick, proving that it could be done without the aid of ghosts. The main trick was to be really good at untying and tying knots.

The Ghost Club spent several years drinking other supposed paranormal events and séances until Dickens’s death in 1870. The Club would not form together again until 1882, heralding its resurgence with one of its most well-known members: Arthur Conan Doyle, famed writer of Sherlock Holmes.

He had a profound belief of all things supernatural, even going as far as to believe in the existence of fairies.

And what of Charles Dickens? With all of the things that he disproved, did he ever find proof of what he was debunking in the first place? Did he ever confirm the existence of a ghost?

Hard to say for sure. As far as anyone knows, there was never any record of the Ghost Club finding actual proof of ghosts. Although, keeping records wasn’t quite the organization’s strongest suit.

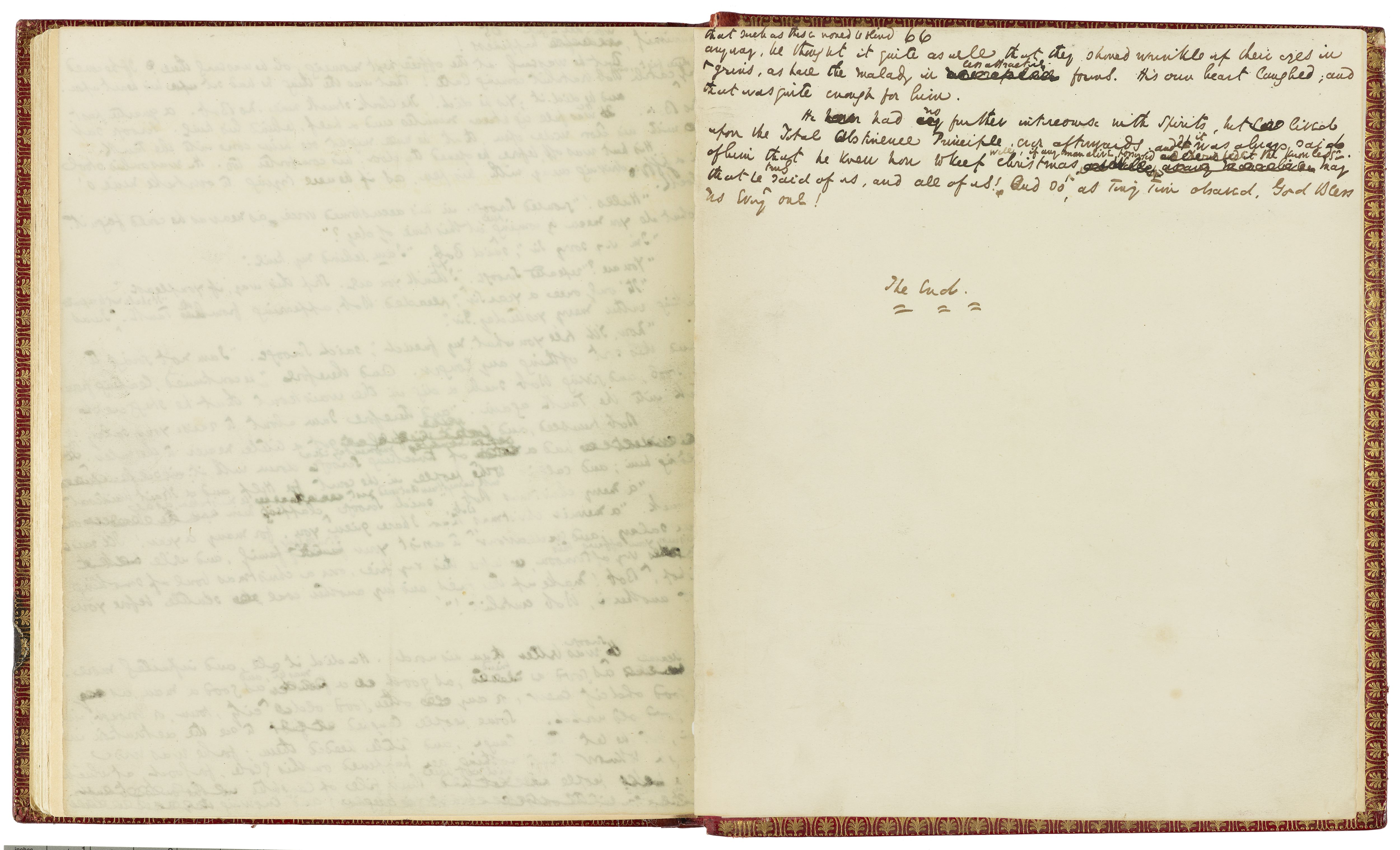

It is interesting to know that five days after his death, Dickens’s spirit supposedly showed up in a séacne in the United States. In the séance, he revealed the ending to his unfinished murder mystery, The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

Unfortunately, the Ghost Club wasn’t there to investigate. Though, in this regard, one cannot really hope for a lot of great expectations.