If you’re in a city as haunted as San Antonio, chances are you’ll be staying at a haunted hotel. With the Battle of the Alamo having taken place less than a minute away, it’s no surprise that the Hotel Gibbs is home to many paranormal entities.

The Battle of the Alamo has infiltrated San Antonio’s past as well as its present. Each year, thousands of visitors flock to the site to pay homage to Texas’ fallen heroes, as well as to wander the grounds which once saw so much bloodshed.

The Hotel Gibbs, smack dab in the Alamo Plaza, isn’t only one of the most haunted places to stay in San Antonio, but it is also one of the most historically significant.

It was in the midst of the 1909 construction of the Gibbs’ building when workers stumbled across something quite old . . . two of the cannons that were used during the Battle of the Alamo.

After the initial shock passed, both cannons were removed from the building’s basement and placed in museums.

One was placed in the Alamo Mission Museum. The other was brought to the Briscoe Western Art Museum (sometimes known as the Jack Guenther Pavilion).

Both of these historically significant cannons can still be found today at both museums.

But, according to more than a few sources, it’s believed that as soon as the cannons were removed from the Gibbs building, all of the ghostly encounters truly skyrocketed.

One strange account came from one of the security guards in the old U.S. Postal Office next-door (now the Hipolito F. Garcia Building and US Courthouse). It was early morning when the guard peered out the window to glance outside.

Out of the corner of his eye, he spotted two shadowy figures pushing a heavy cannon from the Gibbs building to the Alamo. He didn’t think much of it at the time, since he was used to seeing reenactments at the Alamo.

The guard looked away for a second, and when he looked out of the window again, there was no one there.

Scrubbing his eyes with the heel of his palms, the guard assured himself that they’d just moved incredibly quickly.

Later that day, the security guard made a rather striking discovery: there had been no historical reenactments at the Alamo that day.

He came to realize that what he’d seen was the residual energy of fallen Texas soldiers, bringing one of the cannons to fight the Mexican Army.

Upon walking into the Hotel Gibbs, it’s hard not to notice the property’s old world ambiance.

When it was converted into a hotel in 2006, quite a few people vocally admired the property’s historic charm.

One of the builders praised that the Gibbs building was a “leap back in time. It’s a wonderful project, just saturated with history."

Even the Hotel Gibbs’ elegant elevators were an important piece of history, having been the last building in San Antonio to employ elevator operators.

While the elevators are out of commission for the living, the dead are said to still ride the elevator.

On countless occasions, guests have wandered into the hotel to see the elevator doors ping shut; or even see the wisp of a dress skirt disappear inside before the doors slide closed.

Annoyed that they can’t use the century-old elevators, the guests often go in search of one of the hotel’s managers.

I thought the elevators didn’t work,

guests say to the employees of the hotel. Their tone of voice isn’t always accusatory - according to Head Concierge Jake - but they are always suspicious, as though the hotel is purposely withholding information.

The only “information” that the Hotel Gibbs is possibly withholding, is the fact that the hotel has more than a few spectral residents hanging around.

Guests have watched with curiosity (or uneasiness) as people dressed from another time period stroll down the hallways, float through the walls or disappear through the guest room doors.

On several different occasions, guests of the hotel have actually entered their room to find that somebody is already there.

As soon as they try to speak, the figure disappears.

Employees, too, have experienced the paranormal at the Hotel Gibbs. They claim to have heard eerie disembodied voices and the tip-tap of unseen shoes. The front desk of the hotel, where Colonel William Travis is said to have died, is particularly active as well.

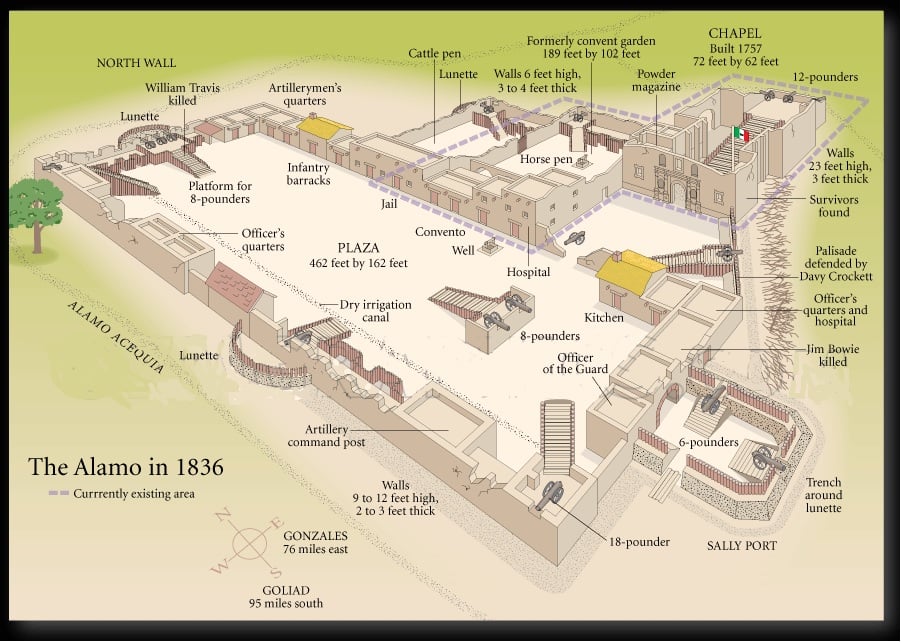

In 1836, the Alamo compound was, quite literally, a massive complex.

The plaza spanned 462 feet by 162 feet, with the exterior limestone walls being nearly two-to-four feet thick.

Stationed throughout the Alamo were large-scale cannons, some 18-pounders, some 12-pounders, but all of which were positioned to do major damage against the Mexican Army.

Not doubt the military compound was a sight to behold as the Mexican troops swarmed in on March 6th.

The layout of the entire Alamo compound during the Battle of the Alamo. To find where General Santa Ana breached the fortress walls, check out the upper left wall where Colonel William Travis is said to have died.

Today, only the old jail, barracks and chapel remain from this grand mission and fort.

But though the Alamo Defenders had laid out the Alamo like a medieval fortress in protection against marauding clans, the 189 Texans were no match for the nearly 2,000 Mexican soldiers who were led by the one and only General Santa Ana.

As opposed to breaching the walls from the front—or what we consider to be the “front” nowadays—General Santa Ana gathered a large portion of his troops by the northwest corner of the compound.

That was where the Mexican Army gained access and breached the mission’s exterior fortress.

Despite the Artillery men’s quarters and the infantry barracks being nearby, there was simply no way for the Alamo Defenders to ward off hundreds of men all at once.

One by one, the Texan supporters fell to the onslaught of gunfire and wielding bayonets thrusting through the air.

Those who witnessed the fighting later commented that the northwest corner of the Alamo saw the heaviest fighting, as well as the heaviest amount of bloodshed.

In fact, some even went so far as to remark that there were so many mangled and dilapidated bodies in that section of the military compound that the soil was saturated—literally soaked through—with all of the blood of the wounded and the dead.

The entire battle, from the first breach by General Santa Ana to the final moments, lasted no longer than 90 minutes.

Imagine inhaling the metallic scent of blood, even as the dirt and sand rose in plumes from the ground, and the sounds of dying men was all you heard.

These were much like Colonel William Travis’ last moments, who was one of the Alamo’s key defenders, and who is said to have been shot and killed right where the front lobby desk of the Hotel Gibbs sits today.

And as for the hotel’s employees, they swear to hear the wailing ghosts of these fallen soldiers all over the property.

The Hotel Gibbs now stands on the site of Maverick's old house.

Not long after the tragic Battle of the Alamo, Texas politician and signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence Samuel Maverick looked at the land and felt the desperate urge to buy it.

Born in South Carolina, in 1803, Maverick was a man quite well off from the start. He attended Yale University for college, having graduated in 1825, before traveling to Virginia where he studied law.

He left South Carolina only after running for a seat in the South Carolina legislature in 1830, where his anti-secession and anti nullification views led to his ultimate defeat.

Seeing no place for himself in his home state, Maverick moved to Georgia, then Alabama before settling in Texas in March of 1835. It was then that Maverick began to involve himself in Texas' initial efforts to claim independence from Mexico.

Well, he mostly involved himself. There was the itty bitty problem of him getting put under house arrest on the orders of Mexican General Martin Perfecto de Cos, General Santa Ana’s right hand man.

With no option for escape, Maverick was imprisoned for nearly a year, in which he and fellow house-arrested mates John W. Smith and A.C. Holmes bore witness to many of the Texans’ trials to leave Mexico entirely.

Samuel Maverick was released from house arrest in December of 1835, just three months before the Battle of the Alamo.

He stayed on site until nearly the last minute, leaving four days before what would become the bloodiest battle in Texas history to serve as a delegate to the convention for Texas Independence.

When he heard of the bloodshed and death, he reportedly told a friend that he felt compelled to come back to the Alamo and purchase the land in which William Travis was killed. Where the haunted Hotel Gibbs stands today.

He said, “I have a desire to reside in this particular spot. A foolish prejudice, no doubt as I was almost a solitary escape from the Alamo massacre . . . "

Maverick constructed his two-story house on that exact same spot in 1850, where the soil was soaked with the blood of the fallen and Colonel Travis had died not some thirty years earlier.

At the turn of the century, San Antonio, Texas, had shed (most) of its Wild West Status as a rough-and-tumble town. Mostly, because it certainly hadn’t shed all of it.

Historic, but often run-down, buildings were being demolished to make way for newer properties. Maverick’s home at the northwest corner of the Alamo compound was one of San Antonio’s architectural victims at the start of the twentieth century.

In 1909, Colonel C.C. Gibbs swooped in and officiated the construction of the first high-rise office building. It was to be eight stories tall, and was built of white glazed brick and terra cotta.

Its interior features were just as magnificent, including one of the city’s first elevators. Though the elevators still exist at the Hotel Gibbs, they are unfortunately no longer in use.

Even so, Gibbs himself was quite a wealthy man. He’d been one of the executives for the Southern Pacific Railroad . . . and perhaps somewhat legendary when it came to drinking.

In one particular account from 1901, the editor at The Tammany Times newspaper wrote an article about Gibbs’ drunkenness, which just so happened to coincide with his meeting of U.S. President McKinley.

In the article, the editor expressed the fact that he had brought Mr. President to San Antonio, and tossed around the idea of introducing him to Gibbs himself, who at the time was an ex-railroad magnate and reformed passenger agent.

The following is the (hilarious) account between the President and Colonel Gibbs, who was a bit in his cups, and narrated by the editor of The Tammany Times:

Speaking of accidents, while in San Antonio I introduced the President to Col. C. C. Gibbs. The President remarked that railroad companies had doubtless to pay larger sums to persons who were hashed up by the cars.

(A lovely, stimulating topic apparently—Ghost City’s interjection)

...That’s where you are fooling yourself, Mr. President,

replied Gibbs, who had been drinking. Seven out of every ten railroad accidents are settled with annual passes. Nine men out of ten are willing to be run over lengthwise by a freight train on a quarter of a mile long for the sake of a few free rides.

I nudged Gibbs to shut up, for the President and the Cabinet members were looking very uncomfortable. Gibbs had forgotten that the President and the whole gang were deadbeating their way across the continent on free passes. It is lucky for Gibbs that he is no longer in the railroad business, otherwise he would be feeling around for his missing head. It isn’t a pretty head to look at, but it is the best Gibbs has in stock. It is, however, infested with brains.

Journalists from back in the day—you’ve really got to love them. (Or hate them, depending on whether you take offense to being called ugly).

Even despite his less than stellar looks, Colonel C.C. Gibbs proved to be one of the most wealthy men in San Antonio, Texas, and his high rise was not superseded by another until the early 1920s when the (also) haunted Emily Morgan Hotel was constructed to be the city’s first medical building.

Even so, the Gibbs building—and now the Hotel Gibbs—has something no other haunted hotel in the area can lay claim to: the Battle of the Alamo’s cannons.

It’s no secret that the bloodiest area of the Battle of the Alamo, would hold on tight to that tragedy even centuries later.

At the Hotel Gibbs, you’re not just in for a treat with the building’s interesting history and beautiful architecture, there’s also a good chance you’ll have to share your space with the hotel’s many unseen guests.

With the supernatural sounds of cannons firing, men crying, and the ghostly footsteps of fallen soldiers, the Hotel Gibbs is certainly the place to be if you’re in the market for a haunted San Antonio hotel.

To hear more about Haunted San Antonio, be sure to join us on our Ghosts of Old San Antonio Tour!

San Antonio's most famous haunted landmark

San Antonio's most haunted Hotel

A popular legend about paranormal San Antonio