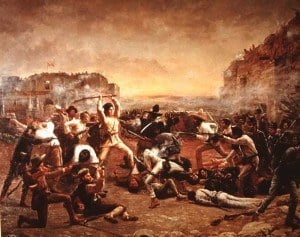

Smoke from discharged weaponry billowed out from around the warring men.

"Remember the Alamo!"

The cry rang out amidst the bursts of canon fire; over the deafening pop-pop-pop of Brown Bess, the Mexican Cavalry’s standard firearm; and the moans of injured men whose last moments were spent on the hallowed church ground.

The Battle of the Alamo in 1836 is indubitably the most remembered fight of the Texan struggle for Independence. The Duke’s (a.k.a. John Wayne) portrayal of Davy Crockett in the 1960 film, The Alamo, only further illuminated the struggle the Texians faced as they strove to free themselves from Mexico’s tightly clenched grip.

But their struggle will be remembered for all of time—if not because of the rallying cry that echoed all throughout America, than because of the large number of spirits which still haunt its bloodshed grounds.

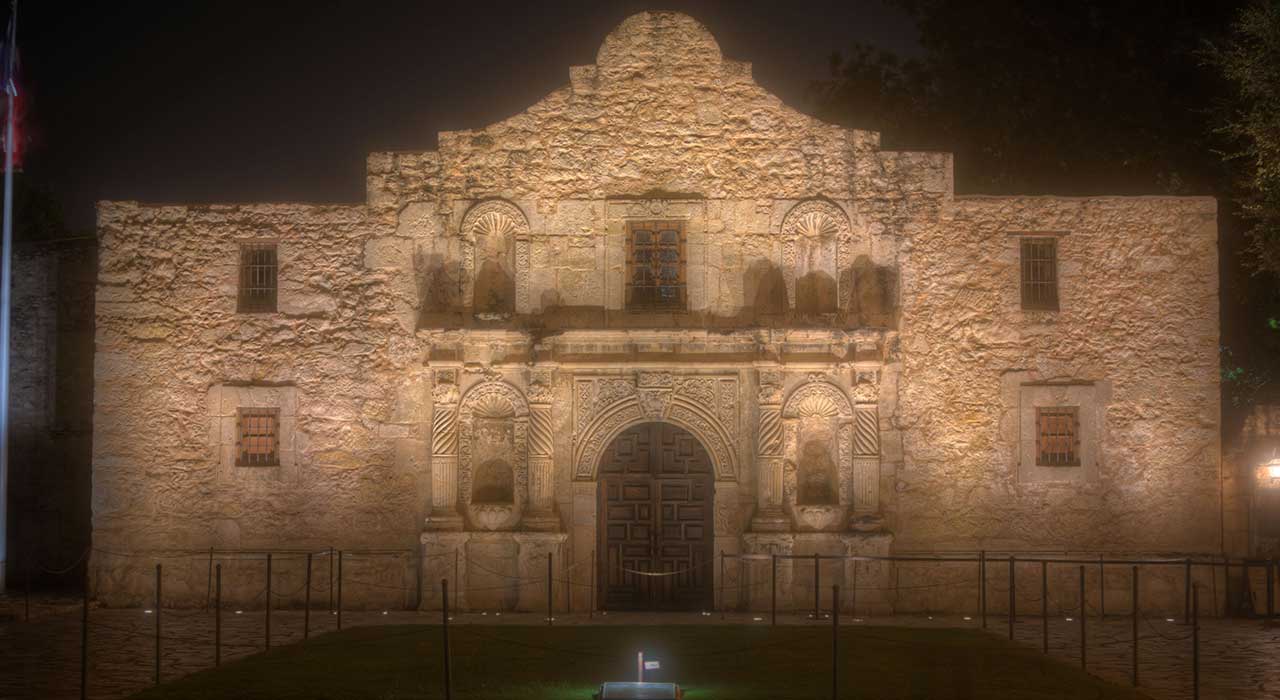

This is the Alamo, which remains till this day, one of San Antonio’s Most Haunted locations.

Way back when, before the Alamo earned its nickname (as the Alamo), it was known as Mission San Antonio de Valero.

The site for the church had been chosen by Father Antonio de San Buenaventura y Olivares after the monks’ first established mission, San Francisco de Solano in the Rio Grande Valley, had taken a dastardly turn for the worse. Following the failed establishment near present-day Nacogdoches—which had the monks fleeing, frightened for their lives—the missionaries gathered under a cottonwood tree along the banks of the San Antonio River.

Father Antonio had recalled the spot from nearly ten years earlier and, as they stood below the cottonwood tree, they decided that it was a very suitable location to build their mission. Although the site was chosen in 1724, work didn't begin on Mission San Antonio de Valero’s stone church until 1744. The church took its name from Saint Anthony of Padua and San Antonio de Valero, the Spanish viceroy at the time the plan had been put into action.

Mission San Antonio de Valero would be the first of five such missions built by the Franciscan monks along the San Antonio River. But all had been built with a singular purpose: to help spread the ideals of Roman Catholicism to the local Native American peoples who inhabited the region.

In 1793, the Spanish had begun to secularize their missions, starting with San Antonio de Valero. For a time, the church became the location of the first hospital in Texas. Soon, it was outfitted as a fort and was assigned a brand new nickname: “Alamo” for the cottonwood tree that Father Antonio had once gathered below nearly eighty years earlier.

As it so happened, “alamo” was the Spanish word for “cottonwood."

The layout of the complex was perfect for barracks, and it was not to anyone’s surprise in the budding city of San Antonio when, by 1803, a company of a hundred heavily armed soldiers and their families moved in. For a period of thirty-two years, the Alamo’s defenders would protect the city from the raiding Apaches and Comanches. But when Mexico earned its independence from Spain in 1821, the people of San Antonio—and the cavalrymen who called the Alamo home—turned to their own hope for freedom from the reigning Mexican regime.

The Texas Revolution erupted on October 2, 1835, near the town of Gonzales.

It erupted, then, but it was certainly not over.

The Texian troops banded together, driving into San Antonio. December 5th commenced the five day brutal struggle with the Mexican troops. For three long days, the fight warred on between the Texians and Santa Ana’s brother-in-law, General Martin Perfector de Cos. What followed was a disturbingly gritty play of house-on-house assaults, snipers seated on the top of roofs as they scoped out their targets below; on the street level, opposing forces clashed together in hand-to-hand combat, where the only sure thing was seeing the face of your killer before your eyes slid closed and the breath left your body.

Both sides struggled to gain control of the city of San Antonio, but it would ultimately be the Texians who won the street fight, forcing the Mexicans authorities to surrender. General Cos signed over everything that the Texians demanded: property, money, ammunition, weapons. Cos moved his troops to the Rio Grande and the Siege of Bexar came to a close.

The win was short-lived.

By January of 1836, the Texians had re-outfitted the old Mission San Antonio de Valero as their home base. When Colonel James Bowie, the famed double-edged knife wielding volunteer soldier, showed at the church, he’d been given orders from General Sam Houston to blow the Alamo up. “Line the walls with dynamite and gunpowder,” Houston must have ordered. “We can’t risk letting Santa Ana in to capture any of the weaponry."

Bowie saw the situation differently.

He took one look at the mission and believed that if the Alamo fell, there was nothing—no barrier, no other defense—to keep General Santa Ana from infiltrating and recapturing the rest of Texas. No, the Alamo would not be blown to smithereens.

(Not to mention the fact that Colonel Bowie did not want to have to move two dozen cannons with only twenty-five men at his disposal. Smart man, that James Bowie).

James Bowie and his twenty-five volunteers were not alone for that much longer. When Colonel William Travis showed up at the Alamo, he did so by bringing a battalion of more than a hundred military men.

Still, the sum 140 men were not enough—surely not enough to go after General Santa Ana’s troops, which numbered to over a thousand cavalry men. Travis was in desperate need for more help. He penned the government in Texas. He sent one frantic missive; and another; and another.

There never was a response, and Santa Ana’s troops were quickly closing in.

For what it was worth, Luck shined down on Bowie and Travis’ men on February 19th, when a group of twenty volunteers arrived with the notorious Davy Crockett at the helm. Crockett was a man of his day: he’d reportedly killed 108 bears in eight months, and supposedly rode alligators as a work out. To many, Crockett was certifiably insane, but he was perfect for the Texas Independence cause. He rallied behind with the other supporters, and helped to round out the number of Alamo defenders to 189.

189 Alamo defenders against more than 1,500 Mexican soldiers.

The odds were not in the Texians’ favor, but they dug deep.

In his last plea to the Texas government, Colonel William Travis wrote that their efforts at the Alamo would either earn them victory, or they would die trying.

Not four days later, General Santa Ana and his troops swarmed in, capturing the City of San Antonio. At the historic San Fernando church, he rose up a red flag. The red indicated that he would he would leave no survivors if the revolutionaries did not surrender.

Their Texians allegedly responded with a single cannon blast.

And then the battle began.

The exact details of the Battle of the Alamo are unknown. Not a single Texian soldier survived, save one: Colonel William Travis’ slave, Joe, who was later released by General Santa Ana on the premise that since Joe had not a choice on whether he fought, he could not be held accountable for standing with the rebels.

But the rest? The rest did not make it.

The images that have been passed down through the generations are powerful. Shocking in their almost tangibility.

Travis was one of the first to die, with his rifle tucked against his shoulder as he unloaded it against those who threatened to keep Texas a part of Mexico.

Remember the Alamo.

Davy Crockett, remembered for hoisting his musket up high above his head, using the butt of the firearm as a weapon itself because he’d run out of ammunition.

Remember the Alamo.

And Colonel James Bowie, laid abed with typhoid-pneumonia, shooting at the enemy as they filtered into his room until the opponents’ bayonets rained down and carved his body unto death.

Remember the Alamo.

It’s said that the rallying call could be heard all throughout as the Alamo defenders fought to their very last breath. Their heroism would be stamped into memory for all of eternity, although their physical bodies would be treated as nothing more than a war trophy.

General Santa Ana refused to grant the Texas defenders a proper burial following Mexico’s victory at the ruthless and bloody Battle of the Alamo. Their bodies were mounted on three pyres and lit into flames. Others were buried in mass graves. Others were simply thrown carelessly into the San Antonio River. According to the story, the bodies were later gathered together and placed inside a unmarked grave, but there is little knowledge as to where it might be.

Three weeks later, General Sam Houston would defeat Santa Ana at the Battle of San Jacinto, by present-day Houston some 200 miles east of San Antonio. Their numbers had been greatly hurt by the fight at the Alamo, with over 1,500 Mexican soldiers dead and more than 500 wounded.

At the Battle of San Jacinto, Santa Ana would ultimately admit his defeat. Texas gained its independence.

But the souls at the Battle of the Alamo still remain, haunting the historic mission now as they did even then . . .

It was not long after the battle had ended that the first sightings of specters at the Alamo began to surface.

Mere days had slipped past since the end of the bloodshed when General Santa Ana mandated that the historic church be burned down to the ground. The thought that the Texians might see the mission as a shrine to those who had rebelled against him made Santa Ana furious. So angry, actually, that he ordered his field commander, General Andrade, to bring a group of cavalrymen out to the site and see that the whole place was alit in flames.

Doing as he was told, Andrade agreed and sent his men.

When they arrived at the Alamo, however, they were quick to turn back around and return to the Mexican Army camp.

Andrade demanded to know of why they had not completed the task.

Shaken and white-faced, one of his men stepped back. He regaled Andrade of the six diablos who had stood before the Alamo. Each spirit had held a flaming sword, encircling the group of soldiers as they blocked the entrance to the mission. They’d feared destroying the church and what might happen to them if they did.

Rumors circulated that entities protecting the Alamo were those men who died during the battle, while others claimed that vigilant specters must have been the old Franciscan monks guarding their mission.

But General Andrade only scoffed at the tale of warrior ghosts and the terrified expressions on his men’s faces. He’d go there himself, then. He enlisted a few men and set off toward the Alamo, Santa Anna’s orders to burn the place down ringing loud in his ears.

When he arrived, he directed his troops to the Long House Barracks. Only this time, instead of the sword-wielding ghosts at the front gates, Andrade spotted a tall, male spirit rise up on the roof of the barracks. Clasped in each hand was a ball consumed in fire. The specter held out the flaming weapons and the Mexican soldiers dropped to their knees. The heels of their palms dug into their eyes to block out the sight, but it was no good.

They feared for their lives.

Andrade left the Mission well enough alone, hightailing it out of San Antonio with his troops as fast as they could march.

Neither they nor General Santa Ana ever returned to the Alamo, and the mission would fall into ruin within the next ten years.

By 1846, Texas had been annexed into the United States and the old Alamo was then converted into a complex for the US Army. But in 1871, the decision came to demolish part of the old church, leaving only the old barracks and the church.

The dismantlement never came.

When the newspapers voiced the deconstruction of the historic Mission San Antonio de Valero, sightings of ghosts wandering the grounds of the church began to be reported—almost all of them coming from the guests staying at the Menger Hotel, just across the plaza. (The Menger Hotel is also rumored to be haunted).

Those staying at the hotel swore that they’d seen the spirits of a long-ago army marching up and down the path in front of the Alamo; some of the apparitions disappeared into the walls of the building, and others stood guard all night as if protecting the site from anything or anyone who might seek to tear it down.

Rather hastily, plans to alter or tear down the Alamo were put to rest, and it became home to a police headquarters and jail instead . . . though the sightings of spirits never ceased.

Between 1894 and 1897, the local newspaper, the San Antonio Express News published a series of articles which highlighted the almost-freakish paranormal phenomenon occurring at the Alamo. The reports described the ghostly guards which marched up along the roof of the police station; the dark figures roaming the corridors at night; and the distinct sounds of moaning that awoke the staff and the prisoners from their slumber.

Soon, the activity was so vibrant, so alive in its frequency, that guards started to refuse being on the patrol shift at night. The policemen were furious. But no one would take those shifts, in fear of running across one of the many ghosts of the Alamo still haunting the grounds, and the prison was forced to move not that long after.

Long before the Battle of the Alamo occurred in 1836, the site on which the Alamo and the plaza sit was once a cemetery for the city of San Antonio.

Between the years 1724 and 1793, it is estimated that nearly a thousand people were buried on this land. Then, the battle transpired and the number of dead whose blood ran into this soil increased by the tenfold. It is said that often construction workers doing work in the Alamo Plaza sometimes pull up skulls and bones.

Is it possible that many of these souls still haunt the site that marked their graves?

One of the most commonly spotted ghosts at the old mission is that of a blond-haired boy. He’s seen most often in the upstairs left window, which now is part of the Alamo’s gift shop. As the story goes, it is believed that the little boy was evacuated during the Siege of the Alamo. Though he survived, it’s thought that perhaps his parents did not and his spirit returns over and over again to the site where he last saw them. During the month of February, his little ghost is seen most frequently.

Along the outer walls of the Alamo, the ghostly figure of what is believed to be a Mexican soldier has been seen by tourists and locals alike. Meandering the grounds, his hands are always clasped behind his back; his chin tilted down, he shakes his head somberly. Although it can’t be proven one way or another, this ghostly soldier is believed to be General Manuel Fernandez de Castrillon, one of Santa Ana’s commanders, who refused to lay siege to the Alamo. After the last of the firefight on the eve of the battle came to an end, six men were brought to Castrillon to surrender. The general offered the men his protection, but Santa Ana refused this act of truce and ordered the Texians’ executions. Infuriated when Castrillon refused to follow orders, Santa Ana murdered the men himself—hacking them to death with sharp-bladed sabers—and almost killed Castrillon himself.

Various reports have surfaced over the years of seeing the apparitions of a man and child up on the rooftop of the Alamo. The spirits are always seen just after sunrise, but then the image distills, jerks, as the ghostly man wraps his arm around the child and leaps off of the parapet to the ground below. It would seem that these ghostly figures are a case of residual energy, for during the last moments of the Battle of the Alamo, General Andrade and the other Mexican soldiers glanced up and were “horrified” to see “a tall, thin man with a small child in his arms, leap to the ground from the parapet at the rear of the Alamo Church."

Since the close of the Battle of the Alamo in 1836, the number of ghosts and paranormal activity at the old mission has not lessened but increased.

A ghostly guard is still spotted on the south side of the roof, especially on nights when it is rainy or cold.

Visitors of the Alamo, which became a museum in 1905, have expressed feeling very melancholy when wandering through the main chapel area of the mission complex. Some have even felt so depressed that tears leap to their eyes and they are powerless to control their erratic emotions.

Others have reported hearing disembodied voices—whispers, as though the spirits are still experiencing the worry of the impending battle—and phantom footsteps.

It seems that even for those who choose to visit the Mission San Antonio de Valero, the ghosts which still haunt the old church grounds have one, singular purpose for remaining: to make sure that all who visit forever remember the Alamo.

Since 1905, the Daughters of the Republic of Texas have watched over and cared for the historic Alamo. It is open to the public to visit, and is often one of the major stops on nighttime ghost tours!

And if you’re hoping to catch sight of the Alamo’s most spotted ghosts, make sure to visit around the time of the battles in February and March!

San Antonio's most haunted Church

San Antonio's most haunted Hotel

One of the oldest, and most haunted buildings