It was the year 1836 when the structure of 716 Dauphine Street was built. Philadelphia-born Joseph Coulon Gardette had arrived in New Orleans a few years earlier with the hope that he might achieve a modicum of success as a dentist in the Crescent City.

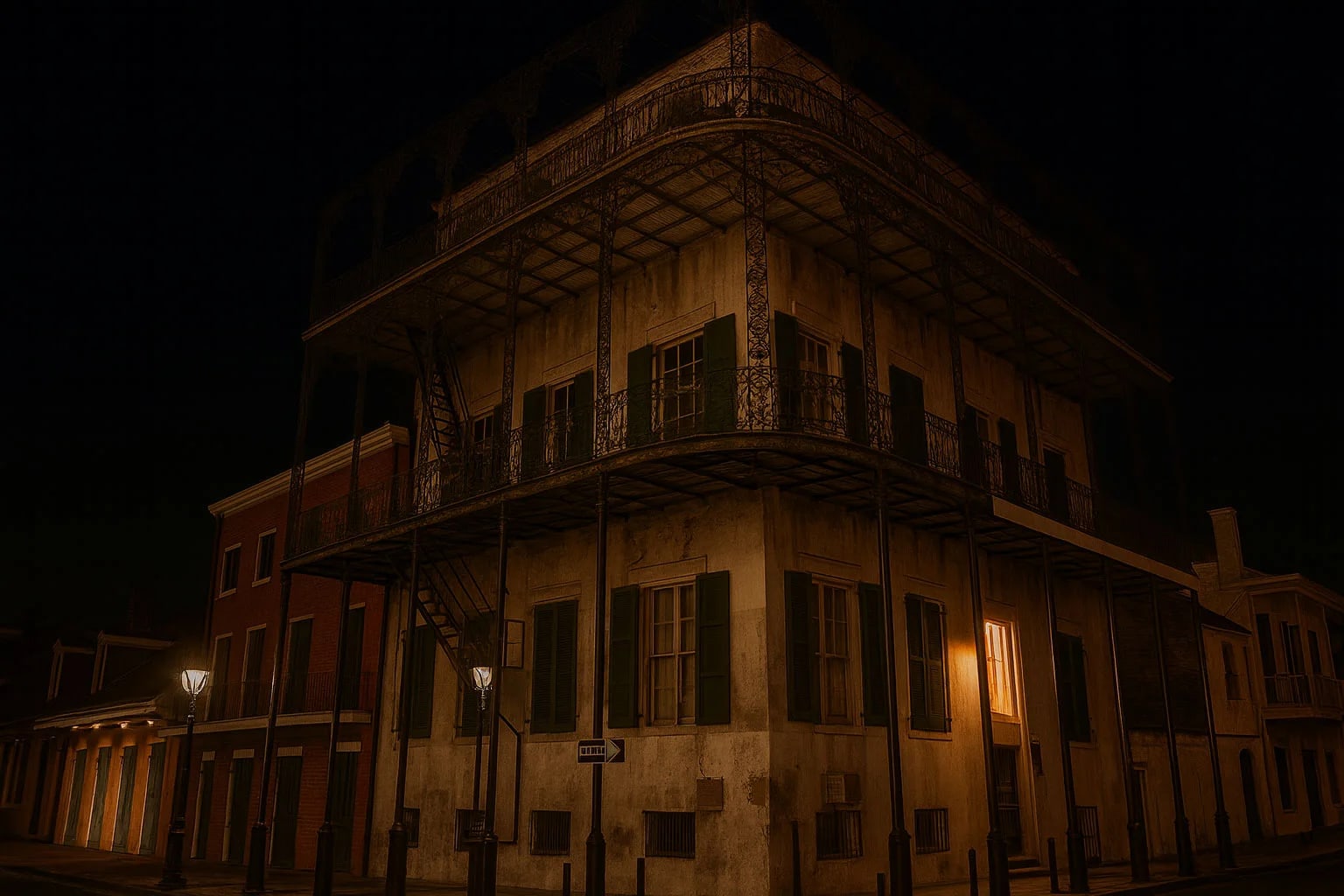

Apparently, Gardette had made the right career move because within four years his business had prospered exceedingly well. He commissioned the local architect Frederick Roy to design him a stately home. The three-and-a-half story mansion was a knock out, and even had a raised half-basement to boot.

Within a few short years, however, Gardette sought to sell the beautiful home at the corner of Dauphine and Orleans Streets. The winning bidder? One Jean Baptiste LePrete, a wealthy bank merchant and plantation owner, who purchased the property for an astounding $20,049 in 1839. LePrete was incredibly wealthy, and by the 1850s, he had hired a builder to add the ornate wrought-iron lace to the balconies.

Desperate Times Call for Desperate Measures: The Arrival of the Sultan to 716 Dauphine Street

LePrete was a man of his day: during the New Orleans Season, he and his family remained at 716 Dauphine while during the other half of the year, the LePretes decamped to their plantation in Placquemines Parish. It worked quite well for the family, this coming and going as they pleased. But then the Civil War erupted in the 1860s and the family's financial stability crumbled. No longer could they maintain the upkeep of the house. The economic downturn following the War was a burden they could not lift, no matter how hard they tried.

According to legend, a Sultan arrived from the Middle East with a large group of people

According to legend, a Sultan arrived from the Middle East with a large group of people

Matters could not have gotten much worse when Jean Baptiste LePrete decided to lease their grand mansion in the French Quarter. He was soon approached by a man of Middle-Eastern descent. He explained to LePrete that his brother, who just happened to be a Sultan, was interested in renting the property. LePrete, so desperate, so keen for any sort of financial help, agreed readily. The contracts were signed, and Jean Baptiste no doubt sighed a breath of such great relief as the tension seeped from his body.

Soon after, a ship arrived in the port of New Orleans. And then everyone disembarked. First were the women, said to be dressed in their finery--silks and satins and gloriously vibrant colors. Next were the eunuchs--or so they say; men dressed in dark military clothing. each carrying a long bayonet. Then, the brother of the Sultan, and then the Sultan himself. Lastly came all of the furniture. There were beds and vases; portraits and rugs; and lo, so many fine pieces that the locals were amazed at the sight of all of those riches!

The procession continued down to Jackson Square, skirted around the grand St. Louis Cathedral, and trekked down to 16 Dauphine, the most majestic home around. What a sight it must have been! The elaborate party then climbed the steps, slipped inside of the old Gardette-LePrete House, and that was that.

Over the course of the next few months, well, 716 Dauphine was a hub of activity. Each night the neighbors heard the tinkling of music carry on the breeze; they heard the giggling of women and the deep, masculine chuckles of the men, and they also heard the distinct sounds of pleasure. The scent of opium, wafting from the open windows, was never far behind. And the New Orleanians? Oh! Well they were rather put out that the invitations to the Sultan's lavish parties were never forthcoming. No matter, they must have thought, as they past by the home for the umpteenth time every night as darkness fell over the French Quarter. The locals were never allowed inside the Sultan's Palace, as it became nicknamed. Goods were placed on the doorstep, if any were delivered, and payment in the form of gold put in its place the very next morning.

Attackers taking over this historic home, killing everyone inside - according to legend, anway

Attackers taking over this historic home, killing everyone inside - according to legend, anway

A Stormy Night of Murder

Then, one night some months later, a storm hit the city. Everyone in the French Quarter buckled down, dimming their candles and closing their shutters. The wind whistled down the street; the lightning cracked overhead. By the next morning, the sky was a blissful blue, as if the rain and thunder had never even passed through. One man happened to find himself strolling down the street, enjoying the crisp air, when he stopped dead in his tracks.

For trickling down the front steps of the Sultan's Palace was blood; it ran down like a river, pooling in the divots of the uneven stone. The unsuspecting man ran to the police station to tell them what he had seen. When the police arrived on the scene, the blood ran thicker, deeper. They looked at one another, all secretly nervous beneath their boisterous conversation. One officer pushed open the door and the collective intake of breath echoed loudly in the otherwise silent house.

Corpses littered the ground; some had been flayed open while others were missing limbs as if some savage beast had sought devilish revenge. The metallic scent of exposed blood lingered in the air. One officer turned and vomited. Another did so, too. The sight . . . the smell . . . Oh Lord, they whispered, who had done such a thing? But the father in through the house they went, the only sight to greet them were the dilapidated dead. In the courtyard, they found the worst crime of all. The soil, it was wet and muddy from the heavy rain the night before, and sticking out of the ground was a single hand, fingers spread wide as if clawing for help.

The Sultan himself had been buried alive.

Who had committed these tragic murders? Who was stained by the blood of the dead? The answer was never truly discovered, although police imagined that the blame lay at the feet of the brother of the Sultan, whose body was never found. Perhaps he had had hired assassins to commit the murders. Perhaps greed and inheritance was the motivating factor--we will never know.

The Truth About the Sultan's Palace: Revealed

The story told above is just one version of many that are told about the Gardette-LePrete House/Sultan's Palace. Oh, the key parts always remain the same: LePrete bemoaning his financial woes, the Sultan's harem moved in, the all-night orgies, and the vicious murder which ends it all.

But is there any historical truth at all to the legend?

Probably not. There are no extant newspapers accounts that our researchers can find that lends credence to the tale. In fact, the only mention of Sultans in the New Orleans newspaper are about those still living in the Middle-East.

LePrete overlooking the city of New Orleans from his balcony

LePrete overlooking the city of New Orleans from his balcony

Jean Baptiste LePrete continued living in this house until 1878. The only truth told in the legend deals with LePrete's financial difficulties. The Civil War had struck his family hard, but there remains no reason to believe that he leased his home to anyone during this period. In 1878, Citizen's Bank foreclosed on the property. One historian even goes as far as to claim that the turn of events was ironic, as Jean Baptiste had been one of the men to found the bank in the first place--in his own parlor at 716 Dauphine, no less!

But by 1922, the legend of the mass massacre had stuck, cemented fully when Helen Pitkin Schertz penned the tale in her book, Legends of Louisiana. For better or worse, the fate of the Gardette-LePrete House was sealed.

In the 1940s, the New Orleans Academy of art had taken up residence, but was forced to close shortly after when too many of its students were drafted during World War II. The once grand mansion then became home to the homeless, and remained as such until 1966 when it was purchased by Frank D'Amico and Anthony Vesich, Jr.. After a large-scale restoration, they converted the property into six independent apartments and it exists today, though under different ownership, just the same.

But who exactly is haunting the Gardette-LePrete House/Sultan's Palace? There have been reports of hauntings for over a century now from residents and visitors alike, and even past owners of the property have experienced paranormal activity a time or two.

Nightly, Ghostly Visitors

In 1979, Frank D'Amico's wife had just climbed into bed for the night. She lived in the penthouse of the building on the upper floor. As she described the event, Mrs. D'Amico then witnessed a dark figure standing at the foot of her bed. It began to approach her, gliding over the floor, when she panicked (rightfully so) and scrambled to turn on the lamp sitting on her bedside table. The lights flickered on, illuminating all of the hidden corners of her bedroom . . . but no one was there. The dark figure which had sent chills racing down her spine had vanished.

For well over a century, people have reported seeing ghosts at the Gardette-LePrete House

For well over a century, people have reported seeing ghosts at the Gardette-LePrete House

The Spirit of the Sultan's Palace

When new owner Nina Neivens purchased the property, she thought very little about the "gruesome murders" that had allegedly occurred in the building. In fact, as she told one newscaster, the only strange, unexplainable phenomenon that she ever experienced at 716 Dauphine were that sometimes personal belongings tended to go missing. Keys, it seems, were a particular favorite for the spirits of the apartment building.

According to historians and paranormal enthusiasts like James Caskey, there seem to be two main ghosts which haunt the Sultan's Palace, and it's unlikely that either one are a result of the nineteenth century murder. The first ghost is that of a Confederate Soldier, who is still haunting the house in his military uniform. The second is the spirit of a woman, who probably lived in the house at some point in time.

What remains incredibly interesting is the ghostly Confederate soldier. No Civil War battles were fought in the local area of New Orleans; it may seem strange, then, that the so-called Sultan's Palace is haunted by one--the truth my surprise you, but we'll have to save that particular tale for our haunted ghost tours of New Orleans. We can't give all of the spoilers away here, but know that sometimes fact is weirder than the folklore.

Residents of 716 Dauphine have experienced all sorts of paranormal activity at this location, including one man who moved into the first floor and half-raised basement not so long ago. While going down the stairs to do laundry, he saw his dog shoved bodily down the flight of stairs by some unseen force. The same dog, it should be noted, refuses to enter the living room unless brought inside by his owner. Animals have been known to have a sixth sense in sniffing out ghosts and spirits, and it seems that this dog certainly knows that something isn't quite right about the Gardette-LePrete House . . .

Visiting the Haunted Sultan's Palace

Today, the Sultan's Palace (or the Gardette- LePrete House) is still a private condominium, which means that it is off limits to tourists or visitors--unless you manage to make friends with one of the owners, of course, and wrangle yourself an invite.

For us regular folk, however, your best chance of visiting New Orleans' most controversial house is to jump on one of the ghost tours in the city. At Ghost City Tours, our much-acclaimed Ghosts of New Orleans Tour stops by this mysterious locale. You'll have the opportunity hear the legend, but more importantly you'll have the opportunity to learn all about all of the true hauntings that no other ghost tour company in the city tells.

The Gardette-LePrete House, known as the Sultan's Palace