The victim of horrifically unjust religious persecution, could Mary Dyer’s spirit still haunt the oldest city park in the U.S.?

As you walk through Boston Common, keep your ears open. For centuries, visitors have spoken of ghostly noises; disembodied voices sobbing or wailing, pleading for mercy, shackles clanging, creaking branches where the old Great Elm used to stand.

If these grounds could talk, they would weep. The Common is home to the Central Burying Ground and former home of the Great Elm, which was used for public hangings. To this day, the crime rate in the area is unfortunately high.

Negative energies from the past seem to linger over this mysterious area.

Along with eerie sounds, witnesses have also reported seeing a woman in colonial

or Puritan-era

dress wandering around Boston Common, often weeping.

This woman is possibly the most prevalent specter that visitors to the Common claim to have seen.

Local legend has it that this may be the ghost of Mary Dyer, whose unnecessary death by hanging serves today as a grim reminder of humanity’s darker side.

Mary Dyer was hanged by the Massachusetts colonial government in 1660. Almost 300 years later, her statue was installed outside the east wing of the Massachusetts State House, just north of the Boston Common.

Could the Common’s sobbing phantom be Mary Dyer?

Many writers through the years have claimed that Mary Dyer was hanged in the Boston Common. That event would certainly lead people to believe her ghost may continue to haunt the area, and public hangings are known to have happened there.

However, more recent research indicates this isn’t true.

Contrary to popular belief, hangings in the 17th century didn’t take place in the Boston Common. The Puritan colonists fancied Boston as a New Jerusalem.

Seeking to keep the city clean,

they conducted executions just outside the city walls. This was directly inspired by executions carried out in Jerusalem.

Instead, hangings took place at the aptly named Boston Neck (also called Roxbury Neck). This was a narrow strip of land that once connected the peninsula of Boston to mainland Massachusetts.

Most agree it existed somewhere along Washington Street, between Dedham and East Berkely.

Mary was not hanged in the Boston Common. For that reason, should we assume that the spirit occasionally seen weeping on the grounds of the Common is not hers?

Not so fast. Mary’s memorial statue sits just off the northeast corner of Boston Common. Memorials exist to make sure we don’t forget our past, and the spirits of those memorialized are known to be seen around them.

It’s not outlandish to think that Mary Dyer’s statue could act as a conduit between our world and the spirit world.

In 1894, a writer for New York’s weekly publication The Independent discussed what he claimed was a long-lost Boston legend: the White Witch of the Common. He told of an apparition that first appeared on June 1, 1750, the 90th anniversary of Mary Dyer’s death.

The writer, Henry Austin, noted that the apparition spoke with a man of great talent who was being held back by drunkenness.

He never revealed what the apparition had said to him, but it sobered him for life. Austin postulated that this inspiring spirit was none other than Mary Dyer.

Henry Austin believed the White Witch of the Common to be an anniversary ghost. These are spirits that appear in the same location on a specific date, often the date of their death.

He further suggested that it was Mary Dyer. Since she was hanged on June 1, and the White Witch appeared on June 1. Dyer is also looked upon as an inspirational figure today, so inspiring greatness would fit her character.

However, we find this unlikely. Sightings of the weeping woman don’t seem to be limited to the anniversary of Dyer’s death, and no other accounts mention the specter speaking to anyone.

Still, we can’t rule out the possibility that this was just one example of a very special appearance. The beginning of many paranormal experiences in the Common.

Mary Dyer and her husband William were Puritans. The Puritans wanted to purify the Church of England, removing remnants of Roman Catholic influence.

Feeling persecuted for their beliefs, a group of Puritan settlers called the Pilgrims founded the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1620.

Upon their arrival, they established their colony with strict Puritan rules. The Puritans had two main concerns: community and conformity.

There was a heavy focus on the latter, with any deviation from Puritan law being handled very seriously, from fines and flogging to banishment or even death.

William and Mary Dyer hadn’t left England with the Pilgrims because they wanted to change the Church of England from within, rather than separating. However, as pressure mounted from King Charles I, they decided they had to leave.

The Dyers set sail for Massachusetts, and in late 1635, they landed and settled in Boston.

Mary struck up a tight friendship with Anne Hutchinson, who didn’t agree with some aspects of the church. Puritans placed heavy restrictions on what women could do, severely limiting their role in society.

Remember that the Puritans left England because they felt that church and state should be separate. In Massachusetts, they founded their new state firmly on the principles of their religion.

This directly tied the church to the state, probably more strongly than had been the case in England.

It didn’t take long for schisms to form. People disagreed in principle with the idea that the church and state should be so tightly intertwined. Anne Hutchinson was one such dissenting member.

Anne Hutchinson had been holding religious meetings for some time, with the Dyers regularly in attendance.

This sort of activity was strictly forbidden by Puritan leaders. Women were not allowed to speak in church, vote, or have any role in government. She would also advocate separating church and state.

In 1637, Governor John Winthrop summoned Anne to answer for her crimes

, which included speaking poorly of some of the ministers. Hutchinson was sentenced to be banished.

As Anne got up to leave, Mary Dyer stood and walked out with her in a gesture of solidarity. As the pair were leaving, someone asked Who is that woman?

And another answered It is the mother of a monster!

Monster

The monster

referred to following Anne Hutchinson’s trial was a deformed stillborn child that Mary Dyer had given birth to.

The event had been kept quiet. To the Puritans, everything had a deep religious connection, and this deformed child could be seen as a sign of God’s displeasure.

Indeed it would seem that Governor Winthrop wanted to see it that way. Winthrop felt that Anne Hutchinson and her allies were heretics, and wanted them all expelled.

He ordered the body to be exhumed so he could examine it. What he described certainly sounds demonic, and heavily exaggerated.

It was of ordinary bigness; it had a face, but no head, and the ears stood upon the shoulders and were like an ape’s; it had no forehead, but over the eyes four horns, hard and sharp; two of them were above one inch long, the other two shorter; the eyes standing out, and the mouth also; the nose hooked upward; all over the breast and back full of sharp pricks and scales.

Though they were neither banished nor excommunicated, William and Mary Dyer left Massachusetts. They went to Rhode Island, which had been founded in 1636 by other outcast Puritans.

They would stay in Rhode Island for more than a decade, with William being heavily involved in politics. However, at some point in 1651, Mary sailed over to England and stayed for several years.

During her time there, she converted to Quakerism. Quakers believe, among other things, that men and women should enjoy equal freedoms.

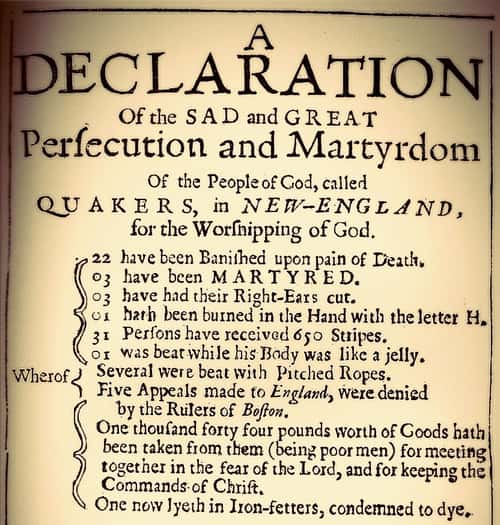

Quakers from England wanted their religious message heard far and wide, and they often faced persecution in England. In 1656, several landed in Boston.

When they began preaching to the devout Puritan populace, they were regarded as heretics.

The presence of the Quakers prompted a swift response from the Puritan government. Laws were created imposing fines on ships that brought Quakers to Boston.

The Quakers themselves would be subject to prison, or to be whipped and forced to labor in Houses of Correction.

Mary arrived back in Boston in the winter of 1657 and was likely aware of the laws against Quakers.

Still, she began preaching her Quaker views and was promptly imprisoned for two months. At some point she was able to get a letter to her husband, telling him where she was.

William Dyer went immediately to Boston, met with then-governor John Endecott, and demanded his wife be released. The governor, knowing of William’s position in Rhode Island, agreed.

However, Mary would have to leave the colony and couldn’t speak to anyone on her way out.

Governor Endecott passed further laws persecuting Quakers in Massachusetts.

Quaker men preaching in the Commonwealth would have their ears cut off, their tongues pierced with hot iron if they were persistent. Women would receive lashings for the same offense.

After hearing that three Quakers had their ears lopped off in Boston, Mary saddled up with four other women and headed back to Boston to protest the inhumane laws.

Unsurprisingly, they too found themselves in prison.

When they were released after a few months, Dyer and three other Quaker men who had made multiple entries into Massachusetts were sentenced to banishment upon pain of death

. This meant that if they ever returned, they would be executed.

William Robinson and Marmaduke Stephenson, two of the men imprisoned and sentenced with Mary Dyer, were caught holding Quaker meetings outside Salem. They were of course arrested again.

Catching wind of this, Mary felt called upon

to go to Boston in support of her friends.

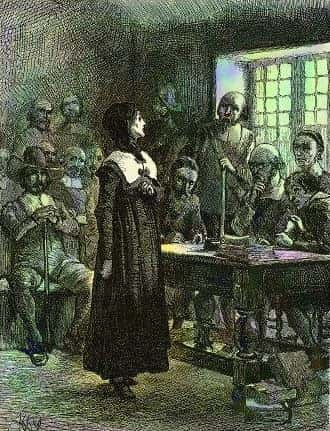

Knowing full well that it meant giving up her own life, Mary Dyer still chose to go to Boston. She was arrested and imprisoned with Robinson and Stephenson.

On October 27, the three Quakers were led to the Boston Neck to meet their end. Mary walked between the younger men, hand in hand, just as she’d done with Anne Hutchinson.

William Robinson was hanged first, followed immediately by Marmaduke Stephenson. Then, the hangman’s noose was placed around Mary’s neck.

Someone shouted Stop! For she was reprieved!

Mary would not hang that day.

William Dyer Jr., Mary’s son, had pleaded for his mother’s life to Governor Endecott. It would’ve looked bad to execute a woman, but the Governor wanted to be sure Mary wouldn’t continue to be a thorn in his side.

Endecott reasoned that if Mary felt the noose around her neck, the icy touch of death inches away, it would discourage Mary from continuing her mission in Massachusetts.

He allowed the hanging to go on as scheduled, but with a dramatic last-second reprieve.

Mary Dyer was briefly returned to her cell, where she penned a letter refusing to accept her reprieve. She felt that she had already given her life for the cause of repealing anti-Quaker laws.

Mary was later removed from Boston by force. She then went to live in New York for a winter.

Not long into her stay there, she caught wind of a letter from the Puritans of the Commonwealth.

The letter was intended to justify the persecution of Quakers to an audience in London. It also explained how they had been so generous in pardoning Mary Dyer.

No doubt enraged by this attempt to downplay inhuman atrocities and unjust murders, she left for Boston once more in April.

Mary was arrested once more upon her arrival in Boston. Again she stood trial, again she pleaded for the unjust laws to be repealed, and again she was sentenced to death. Theologian George Hodges wrote:

She knew by awful experience that the court would keep its word. She had died once, and in the name of God and of the cause and truth for which she stood, she went to die again.

On June 1, 1660, Mary Dyer was once again led to the Boston Neck. She was hung in the same fashion as other Quakers before her and was buried in an unmarked grave.

She would not be the last.

In March of 1661, Quaker William Leddra was hanged in the same manner. Following Leddra’s death, King Charles II demanded an end to the hangings.

Mary Dyer’s legacy is not just about the importance of individual liberties, including freedom of religion. It is about the power of kinship with your fellow man.

Mary Dyer stayed true to those who had been true to her, even upon pain of death

.

When she walked out of the church with Anne Hutchinson, she was selflessly supporting a dear friend. When she visited imprisoned friends in Boston, knowing it would likely mean her death, she was giving her life to expose injustice.

When Mary Dyer returned to Boston a final time, she was dictating that her cause would not be quietly forgotten. She gladly gave her life with the hope that it could inspire positive change. Mary Dyer’s story is one of love for humanity over the love of oneself.

Mary Dyer’s statue can be found just off the northeast corner of the Boston Common, on the corner of Beacon and Bowdoin. As for her ghost, your best chance might be to plan a visit for the first day of June.

Learn more about Boston's most haunted Cemetery

Boston Common is Boston's haunted hotspot

Boston's haunted Library, haunted by Literary Giants