Although we all know of Salem’s Witch Trials, we know little of Salem’s Tituba. Tituba – Salem’s first accused “witch” and the first to confess. Her testimony is even thought to have shaped the trial’s trajectory.

Tituba was likewise the first to incorporate flying or animal familiars into her confession, though the two are now implicit in our image of the witch.

The allegations against Tituba are unsurprising. As an enslaved woman, Tituba was at a legal disadvantage.

Tituba was also an indigenous woman – an easy scapegoat for Salem Village. Tituba’s biography is otherwise unclear.

For example, Tituba is the “Black Witch of Salem,” yet was likely Amerindian. Tituba’s biography is mired in myth and misconception. What do we know about Tituba? How was Tituba brought to Salem Village – or their Witch Trials?

We know little of Tituba’s life before her enslavement. Even Tituba’s ethnicity is contentious. Some suggest that Tituba was native to South America, while others propose that Tituba was African American.

We do know that Tituba sailed from Barbados to New England with Reverend Samuel Parris. We also suspect that Reverend Parris obtained “ownership” of Tituba whenever she was in her early teens.

Yet, Tituba’s origins are, at best, speculative.

The most comprehensive study that we have of Tituba comes from Elaine G. Breslow’s Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem: Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies. In Tituba, Breslaw attempts to demonstrate that Tituba was not Barbadian and instead speculates that Tituba was brought captive from South America.

Breslaw later traces Tituba to an Arawak-speaking group in present-day Venezuela, proposing that Reverend Samuel Parris captured Tituba on a kidnapping expedition.

Tituba married John Indian in 1689, though John’s origins are also enigmatic. John, recorded in contemporary documents as “John Indian,” “Indian John,” or the “Indian Man,” was enslaved to Reverend Parris near the time of Tituba and lived with Tituba in the Parris household.

Reverend Parris brought Tituba and John to Boston, where Parris found his bride. Parris then brought Tituba and John to Salem Village in 1688, where they married in 1689. Tituba and John may have also had a daughter by the name of Violet. Resources on Tituba are limited, though extensive research has been attempted.

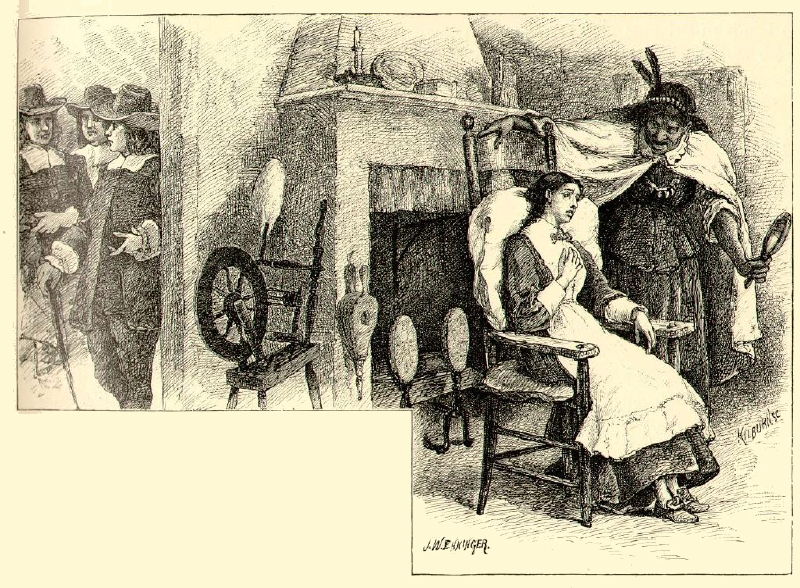

Scholars believe that Tituba acted as the household servant, taking her meals with the Parris’ daughters and sleeping beside them at night. Tituba was presumably close to Elizabeth (Betty) Parris, who would later accuse her of witchcraft.

In 1692, Betty Parris began to exhibit strange behavior. She and Abigail Williams were “struck dumb,” choking and convulsing, uncontrollably thrashing their limbs.

The Parris Household applied ointment to the “afflicted” girls, yet their remedies could not restore them. Betty and Abigail continued to “flinch, crouch, and gabble.” Reverend Parris began to believe that Betty and Abigail were bewitched. Even Dr. Williams Griggs confirmed that the girls were under an evil hand.

In response, Tituba and John concocted a “witches’ cake” comprised of rye and urine. The urine belonged to Betty and Abigail, as the recipe demanded the bodily fluids of the afflicted.

Tituba was told that the witches’ cake would reveal their bewitchment: if she fed the cake to a dog, and the dog exhibited symptoms similar to the girls, the girls were possessed. While John collected urine from Betty and Abigail, Tituba baked the cake itself.

Of course, the cake revealed nothing.

Contrary to popular thought, the witch cake was an English superstition. Although it’s inaccurately described as a voodoo practice, Mary Sibley was the one to advise Tituba throughout the process.

In fact, the witchcraft that Tituba later admitted to was not culturally African or Caribbean, but English.

Reverend Parris denounced the practice, claiming that Tituba had gone “to the devil for help against the devil. Sibley was suspended from communion for encouraging the cake, though she was later readmitted.

Sibley, unlike Tituba, was not charged with witchcraft.

Tituba was accused of witchcraft the following day. Betty and Abigail declared that Tituba had appeared to them as a spirit. Their accusation was later used against Tituba as “spectral evidence,” or the eyewitness accounts of the afflicted gathered through dreams, hallucinations, or visions.

Reverend Parris also struck or beat Tituba to force her into a false admission, leading some to believe that Tituba confessed to avoid further mistreatment from Parris.

Tituba would not have expected the witchcraft conviction. Witchcraft accusations were typically used against marginalized or cantankerous Europeans, not enslaved peoples. Tituba was nevertheless an “easy scapegoat” as a person of color, and allegations of voodoo or devilry proliferated the examination.

Tituba denied the accusations at first, though later “admitted” to witchcraft. She may have thought that a false admission would spare her prison, especially if she identified fellow witches.

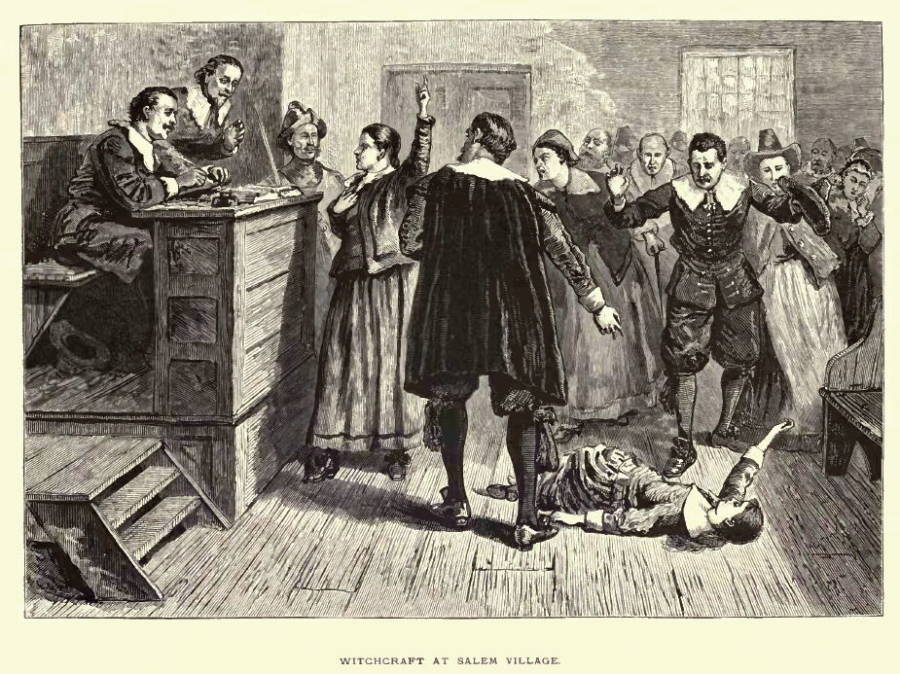

Tituba’s was an unusual testimony. She alleged that she rode on sticks with Betty and Abigail. Tituba also claimed that two rats, one red and one black, had demanded that she serve them. Tituba then confessed to pinching the girls and signing the Devil’s Book.

Tituba even maintained that a “tall, white-haired man from Boston” had demanded she assault Betty and Abigail. Tituba supplemented her confession with references to a “hog, a great black dog, a red cat, a black cat, a yellow bird and a hairy creature that walked on two legs.”

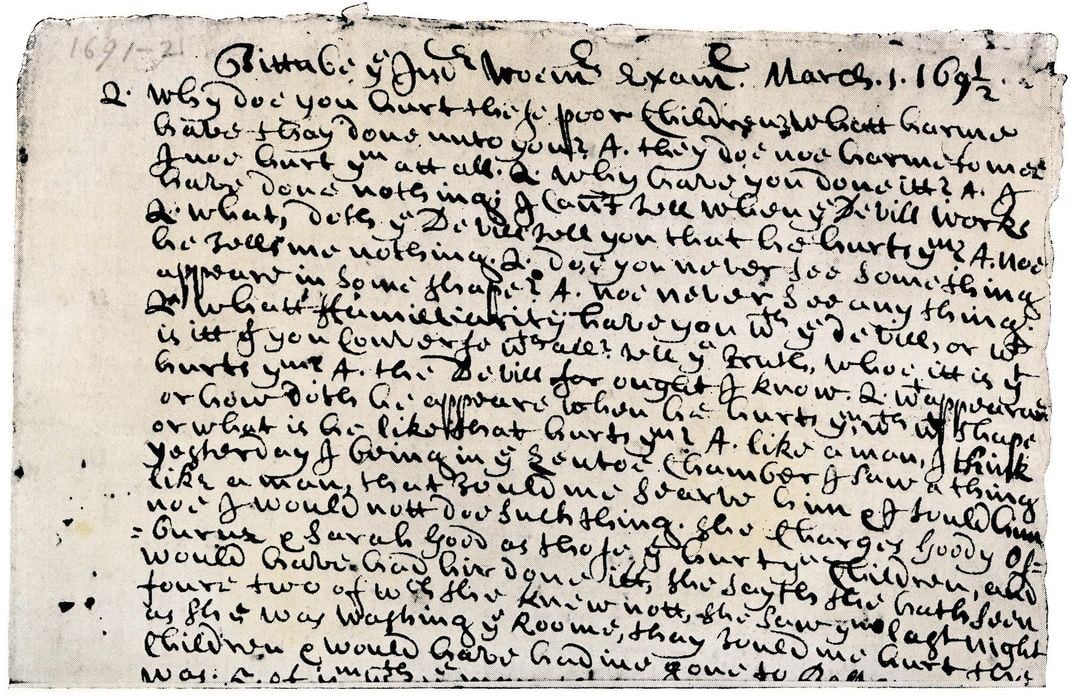

Tituba, along with Sarah Good and Sarah Osburne, was the first arrested. She was then taken to Nathaniel Ingersoll’s Tavern, interrogated by Judge John Hathorne and Judge Jonathan Corwin. The three were examined for “witches mark,” identified as any “unnatural” bodily growth or feature. These “abnormalities” indicated witchcraft to Salem Village and were assumed to suckle a witch’s familiar.

Although Hannah Ingersoll found no witches mark upon either three, Tituba confessed to witchcraft while naming the other two as witches:

Tituba then detailed her consorts with Satan, though professed her love for Betty Parris. Tituba apologized, arguing that she had never meant to hurt the child:

Sarah Osburne and Sarah Good maintained their innocence, yet Good blamed Tituba and Osburne for black magic. Soon arrests were made for others who had been unjustly accused, such as Martha Corey, Rebecca Nurse, Elizabeth Proctor, and Sarah Cloyce.

Tituba was the first to confess to witchcraft in Salem Village. She may have been unable to maintain her innocence. As an enslaved woman, Tituba was socially disadvantaged.

Tituba may have also understood that Puritans were quicker to forgive a false confession than they were to allow or accept defiance.

In Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem, Breslaw further affirms how “the epidemic of strange behaviors and accusations did not spread to other victims until after Tituba’s arrest and her several testimonies.” Brew slew continues that the “conclusion of Tituba’s remarkable confession marked a new chapter in the witchhunt episodes of New England.” Tituba’s confession is therefore critical to understanding Salem’s trials and executions.

Her false admission was indisputably imaginative. Some believe that Tituba’s confession determined the shape of the witch trials, leading others to declare that they had signed a Devil’s Book or consorted with a demonic familiar.

Tituba likewise provided the longest testimony, helping visualize the Salem Witch Trials. It was even Tituba who helped create the image of the flying witch.

Tituba adapted her testimony throughout the trial: her co-conspirators went from nine to five hundred, the “tall, white-haired man from Boston” culprit became a “short, dark-haired man from Maine.” Tituba even recounted her confession, claiming "that her Master did beat her and otherways abuse her, to make her confess and accuse her Sister-Witches."

Yet, Tituba’s renunciation of witchcraft did not cease Salem’s Witch Trials. Tituba’s recant received little attention and was neglected in court records and witness reports.

By June of 1692, Massachusetts law prohibiting death by hanging was resurrected and reinstated. Executions were allowed for witchcraft. Nineteen were hanged at Proctor’s Ledge. Their bodies were unceremoniously castoff in its crevice.

Nevertheless, Tituba was spared. The jury refused to indict Tituba, finding her “not guilty” for lack of evidence. She spent thirteen months in Salem Jail yet was released on bond.

Parris refused to pay Tituba’s bail, and it’s unknown who initiated her release. Tituba was then sold to an anonymous person for the price of her debts, disappearing from record. John was presumed to be sold alongside her. Nothing else is known of Tituba.

Although Massachusetts later restored the names of Salem’s victims, even returning their property, Tituba received nothing. Tituba had been an enslaved woman without property or rights and was denied restitution.

Tituba’s legacy will continue to linger. To Breslaw, Tituba created “a new idiom of resistance by overtly submitting to the will of her abuser while covertly feeding his fears of a conspiracy.”

We understand today that Tituba was unjustly accused of witchcraft. Yet, Tituba was a victim of colonialism as much as she was of Salem’s Witch Trials. Her status as an enslaved woman left her legally disadvantaged in Salem Village. Her life was as inequitable as was her examination.

We are not so far from Salem’s Witch Trials as we’d like to believe. We, as a nation, engage in our own “witch hunts” – targeting the marginalized or disadvantaged. With hope, Salem’s Witch Trials will inspire us to distance ourselves from the intolerance of our ancestors.

If you’d like to pay your respects to Tituba, stop by the Salem Witch Trials Memorial. The monument established a marker for Tituba in 1992, canonizing Tituba in America’s history. The memorial can be located at 24 Liberty Street of Salem, Massachusetts.

You can also visit the Salem Village Parsonage, Tituba’s former residence. The Salem Village Parsonage can be found at Rear 67 Centre Street of Danvers, Massachusetts.