A Family Frozen in Time

The Willink House in Savannah, Georgia, is both like and unlike any of the other houses in Savannah's Historic District. It's considered different, because aesthetically it would appear much more at home in Cape Cod, Massachusetts's peninsula. But while the Willink House's architectural design may be in the Cape Cod-style, its history is solely Savannah's. Like many historic properties in this riverside city, the Willink House has been moved from its original location to a brand new one, sitting currently on the NW corner of Price and St. Julian Streets. And, if you're looking for one more reason why the Willink House truly fits in within the boundaries of Savannah, it might just be because it's incredibly haunted. After all, Savannah *is* considered to be one of the most haunted cities in the United States.

Fast Facts

- •Built in 1815 for the Dutch merchant family

- •Entire Willink family died of yellow fever in 1820

- •Five family members died within three weeks

- •House remained empty for decades after the tragedy

- •Known for gentle, sorrowful paranormal manifestations

The History of The Willink House

It Started with Henry F. Willink

We can't talk the history of the Willink House without first mentioning—and discussing—its first owner: Henry Frederick Willink. Born in 1825 (or 1827, according to some accounts), Willink, Jr. came from decidedly new money. His father, Frederick Henry Willink, was a German immigrant and merchant. Like many newcomers to America during the nineteenth-century, Willink, Sr. had big dreams involving lucrative cash and, you guessed it, unimaginable success. By 1860, at the whopping age of 75, Willink, Sr., had amassed nearly as much as $59,000 as well as 23 slaves.

He'd done well for himself, and he expected the same of his son.

After attending Chatham Academy in Savannah, Willink, Jr. (from here out mentioned as plain old "Willink") worked on his father's shipyard for some years before moving to New York to do similar work. It was backbreaking, tiring, but Willink had a fire lit under him, the same fire that had ignited under his father and pushed him to success. Nine years after landing in New York, Willink returned home to Savannah in 1851, with the intention of beginning his own shipbuilding business.

And so that's what he did—for the most part, in any case.

Willink and his Ironclads

The Confederate Navy had a problem at the start of the Civil War—all right, it's likely they had a lot more than a single problem, but there was one particular that truly stuck out.

They had no ships that were equal to those being used by the Yankees, i.e, the Union Navy.

The first ironclad to be produced on Willink's shipyard went by the name C.S.S. Georgia, but quickly became routed as "The Ladies Gunboat." If you're thinking it's because the C.S.S. Georgia was effeminate or weak, you'd be wrong. As it just so happened, the gunboat had been paid for by the Ladies' Gunboat Association, of which they had invested $115,000 into its construction.

A whole lot of money now, but then such a sum was almost unheard of. But as imposing as The Ladies' Gunboat may have appeared wading through the water, it was a lucky stroke of good fortune that the blasted haul didn't sink to the bottom of the Savannah River. For as pretty and inventive as the C.S.S. Georgia was, it was more equipped to function as a floating battery as opposed to a vessel at war. She was so heavily burdened by armor and weaponry, that to imagine her sailing down the Savannah River must have been like watching a cow sneak through a doggy door.

It simply wasn't done.

When the public bore witness to the eyesore that was The Ladies' Gunboat, they flew into hysterics. The Ladies' Gunboat Association were quick to respond: the* C.S.S. Georgia* was supposed to act as a floating battery, you see. "It had been the intent from the start," the committee told the city, "to have not an ironclad ram, but a 'Floating Battery with Propellers.'" You can imagine that the City of Savannah and the Confederate Navy were not amused.

Throughout this entire debacle, Willink was working tirelessly to get Stephen Mallory, the Secretary of the Confederate Navy, the second ironclad he'd promised to the Navy. Earlier on, Willink had traveled to Richmond, Virginia, with the intent of building a series of ironclads. A model had been sent to Richmond, to which Mallory allegedly responded: "If you are disposed to enter upon the construction of a vessel of this description, and can complete her within a reasonable [time], I will be glad to confer with either or both of you as early as practicable."

"Practicable" to Willink was at least six months time to complete two ironclads. Mallory had other plans.

"Four months," he instructed Willink.

Willink agreed, but probably only because he had no other alternative. He didn't sign a contract until the end of March 1861. Much like how operations worked on his gunboats, Willink did not receive payment until he hit certain benchmarks on the building process. Even so, he immediately got to work by cutting live oak on Ossabaw Island and bringing them up the Savannah River.

Building the War Vessel of all War Vessels

Unfortunately, this title is a bit of a misnomer. Willink certainly built a war vessel, but like The Ladies Gunboat, his second model, the C.S.S. Savannah was also monstrous in size and just as inconvenient when in the water. It was also, according to one account, pretty much an assault on her crew.

Author James Caskey of Haunted Savannah made note of one particular crew member on the C.S.S. Savannah who complained: "There is no ventilation at all. I would defy anyone in the world to tell when it is day or when night if he is confined below without any way of marking time . . . I would venture dos ay that if a person were blindfolded and carried below and turned loose he would imagine himself in a swamp, for the water is trickling in all the time and everything is so damp."

Not exactly the finest words of praise for Henry F. Willink's work of art. The ship was destroyed by Confederates in 1864, in an attempt to avoid capture by the Union troops. (Only, it seems that Willink may or may not have aided the Confederates in doing so, so that the Union charged him with aiding the enemy. Willink admitted he'd done so, and, having been so impressed with his blunt honesty, the Union agreed to let him walk free.)

Even so, Willink nevertheless remained one of the integral figures in Savannah during the Civil War. Even when he was ordered to cease production on his shipbuilding and to remove obstructions from the Savannah River—of which he has not happy to do, but complied because the obstructions had begun to sink the barriers—Willink never lost sight of his father's legacy and his own ambition for success.

After the Civil War had come to an end, Willink continued to orchestrate and run one of the largest shipyard businesses in Savannah. He organized the Southern Wrecking Company, built a marine railway on Hutchinson Island and involved himself in various entrepreneurial ventures on the Savannah River.

If that was not enough, in the 1870s he rose through the ranks to become the manager of the Savannah Dry Dock Company. In 1877, he was elected as one of the alderman of Savannah. (According to one 1879 issue of the Savannah Times, it's possible that Willink had acted as alderman in the 1860s as well).

Where Willink went wrong was not in his professional life, but rather his personal one—but we'll revisit that particular story in the Ghost section of this article.

Relocating The Willink House to 426 E. St Julian Street

It was mentioned earlier that The Willink House was moved from his first location, just south of Oglethorpe Avenue at the corner of Price and Perry Streets, to a new location.

There's a bit of discrepancy on when The Willink House was even built; some estimate it to have been constructed around 1845. It might not seem that big of a deal, except for the fact that: According to various accounts, Willink had not even returned to Savannah from New York City at that point. (Semantics, I guess).

Willink lived at the property for only about ten years before he sold it to another, and it continued down the line of various owners until the twentieth century when it was moved to its current location.

By 1955, many of Savannah's historic homes faced immediate danger of being torn down to make way for modern buildings, parking lots or just about anything that wasn't a slightly decrepit building dating to the pre-twentieth century. In fact, much of Savannah's lovely Historic District was nothing but a slum.

The preservation movement kicked in during the early 1900s, in which a group of women banded together and refused to see their beloved city be torn apart by trucks and impartial workers. They formed the Historic Savannah Foundation to save the 1820s Davenport House, which is now the foundation's home base, but The Willink House was also at one time one of the properties saved by the Historic Savannah Foundation in 1964.

But though the property can no longer be found on its original tract of land, homeowners of the now-426 E. St. Julian Street have admitted to hearing strange, unexplainable house within Henry F. Willink's old home.

And their only answer is that the almost two century old Cape-Cod style home is haunted.

The Ghosts of The Willink House

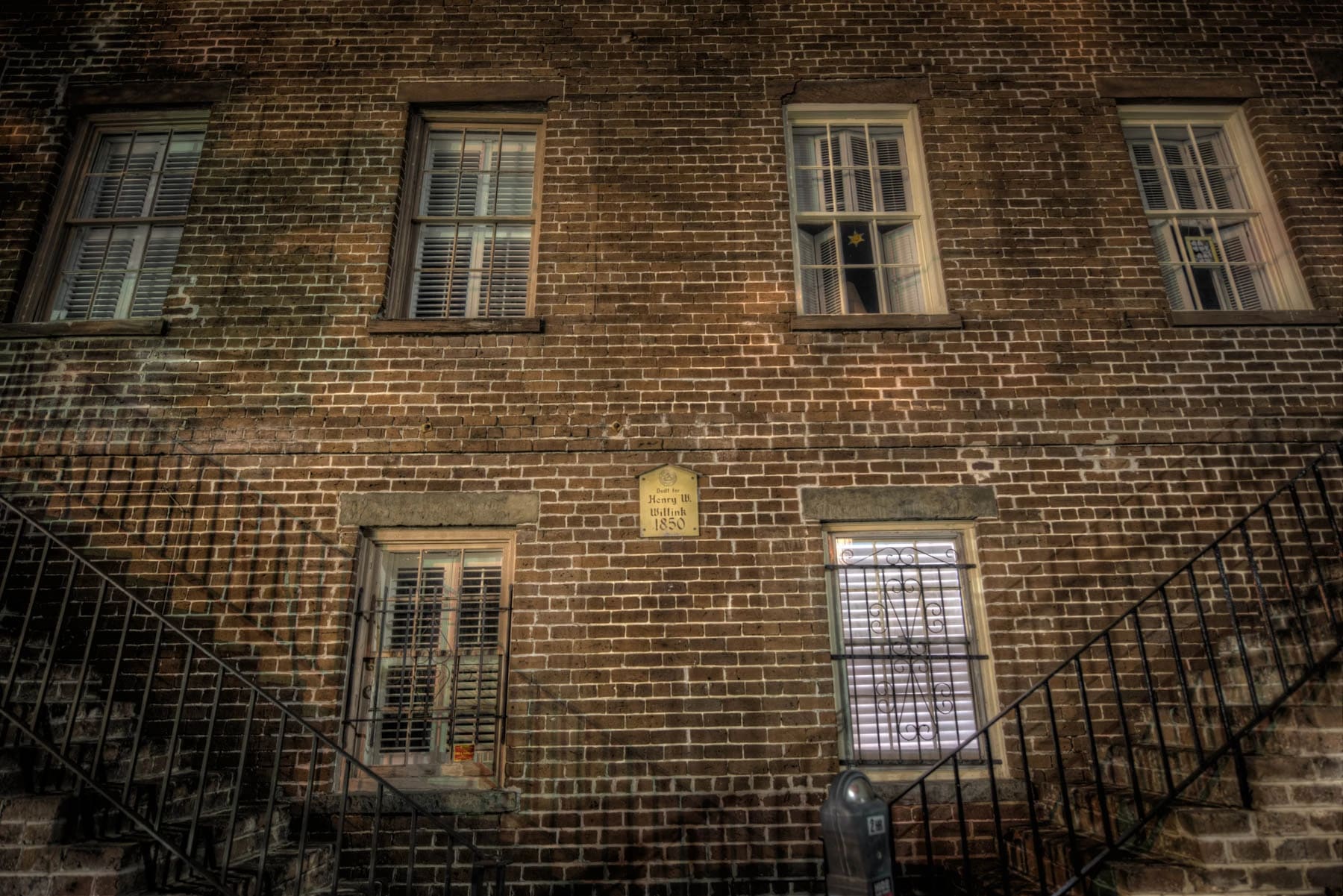

(Note the above photo--looks a bit different than the original "haunted house"? Well, after Henry F. Willink moved out of his much smaller, humbler abode, he moved into the brick building above. More fitting for a man of extreme wealth, of course.)

Haunting the Willink House: Tragedy Strikes

Earlier I'd mentioned that Henry F. Willink's personal life was a bit on the rocks—I was not exaggerating.

His shipyard was his pride and joy—by 1860, he'd already amassed a small fortune. Not only was he the builder and owner of the shipyard, but he also owned about $10,000 in property value in addition to owning five enslaved people.

But while his wealth was persistently growing, Willink knew tragedy first hand. On one particular day, he turned to his wife and asked if she'd like to accompany him to the shipyards. She immediately said yes, no doubt thrilled at the prospect of spending time with her husband.

They arrived shortly after, and for a small time everything was just fine. But then Mrs. Willink misstepped and went tumbling over the ship's railing. Her body crashed into river down below. Willink launched into action, but it was much too late—Mrs. Willink did not know how to swim and, caught amidst the tumultuous current, her heavy skirts weighed her down until she drowned.

Henry Willink was inconsolable. After his wife's death, he did nothing but work. His nights were restlessly kept, and more often than not he spent his time pacing inside his home before deciding to return to the shipyard in the dead of night.

On one dreaded night, Willink made the same mistake as his deceased wife. As the story goes, he was working on one of his ships when his wife's apparition manifested right before him! Shock ricocheted through him. Willink stepped back to gather his riotous thoughts—he knew she was dead, but there she stood before him!—when he mistook the edge of the ship and slipped overboard.

Willink, thankfully, was saved from the same fate that had taken his wife's life. Even so, the sounds of Henry Willink storming outside of his house and the door slamming shut behind him, was a reoccurrence that Willink's neighbors grew to recognize quite well . . .

And so they did, even after Willink's rather mysterious death, which was allegedly never documented. For nearly two centuries now, even with consideration for the property's move, owners of The Willink House have heard the distinct sound of heavy footfalls heading toward the front door.

Even neighbors or passerby have routinely heard The Willink House's front door creak open before slamming shut—even when there is clearly no one actually leaving the house.

Henry F. Willink's spirit, it seems, is unable to leave the home he shared for a short time with his wife. Or perhaps it's simply that his ghost is unable to leave without her.

The Ghosts of School Children

After Willink moved from his home, it's said that the property became a secret school for African-American children during the years leading up to the Emancipation Proclamation.

During that period, such schools were deemed illegal—the South was becoming increasingly worried that enslaved people who were literate posed a much bigger threat to the institution of slavery than those who could barely scrawl their own name.

But the fear transcended into a much bigger issue: slaves who congregated, or even those who were free, were dangerous. If they gathered together, ideas could be tossed around and revolts slid into action. City officials criminalized the gathering of African-Americans, free or enslaved, whether it be at church, a school, or simply in a park.

For The Willink House to have functioned as a school for African-American children would have been a crime. As the story goes among the locals in Savannah, a white female teacher had taken up the school in secrecy so that she could teach reading and mathematical skills to enslaved children. Legend has it that she coerced them into learning by bribing them with sweets, which the children agreeably snacked on—but only if they solved the problems correctly.

A reward, if you will.

The teacher herself would have no reward.

Her secret school was unveiled, and city officials gave her a choice: she could either accept the heavy fine and an arrest for breaking the law, or she could leave Savannah forever.

With her heart broken, the teacher visited the school one last time to say good-bye to all of her students. It's believed that she never returned again—although the same can't be said for the After Life.

In conjunction with hearing the ghost of the angry, brokenhearted Henry Willink, owners of 426 E. St. Julian Street have also caught the scent of candies in the house as well. Perhaps the spirit of the teacher, or even the school children still haunt the building?

Owners have sworn up and down to find sweets appearing in what they claim to be rows of mathematical problems. Others have claimed to find candy moved from their kitchen to other rooms, leading them to no doubt wonder if the school children are enjoying their snacks or trying to gain attention for their spectral presence.

Author James Caskey wondered in his groundbreaking book, Haunted Savannah, if the children return to the old school house to let the living know that they have not "forgotten their lessons, or their teacher's kindness."

Whether the school children have stuck around for the sweets or their beloved children, The Willink House continues to bear the spirits and spectral activity of those who have either been wronged directly or have faced the ultimate tragedy: death.

Visiting The Haunted Willink House

Today, The Willink House is still privately owned. (There are even photos on Zillow from the last time it was on sale — go take a peek, I know you want to).

What this means is, unfortunately you are unable to enter the haunted Willink House or you'll have the opportunity to face the owners' wrath when they find you inside their property.

But! If you'd like to take a walk by and see if you too hear the front door being violently thrown open, be sure to walk by 426 E. St. Julian Street in Savannah's Historic District.

Visitor Tips

- Evening visits offer the most family activity

- Listen for Dutch conversations and children's voices

- The nursery is particularly active and emotional

- Bring respect for the tragedy that occurred here

- Photography often captures multiple family figures

- Children visitors are especially sensitive to the young spirits

- EMF readings spike during family gatherings

- Prepare emotionally - this is a very moving experience